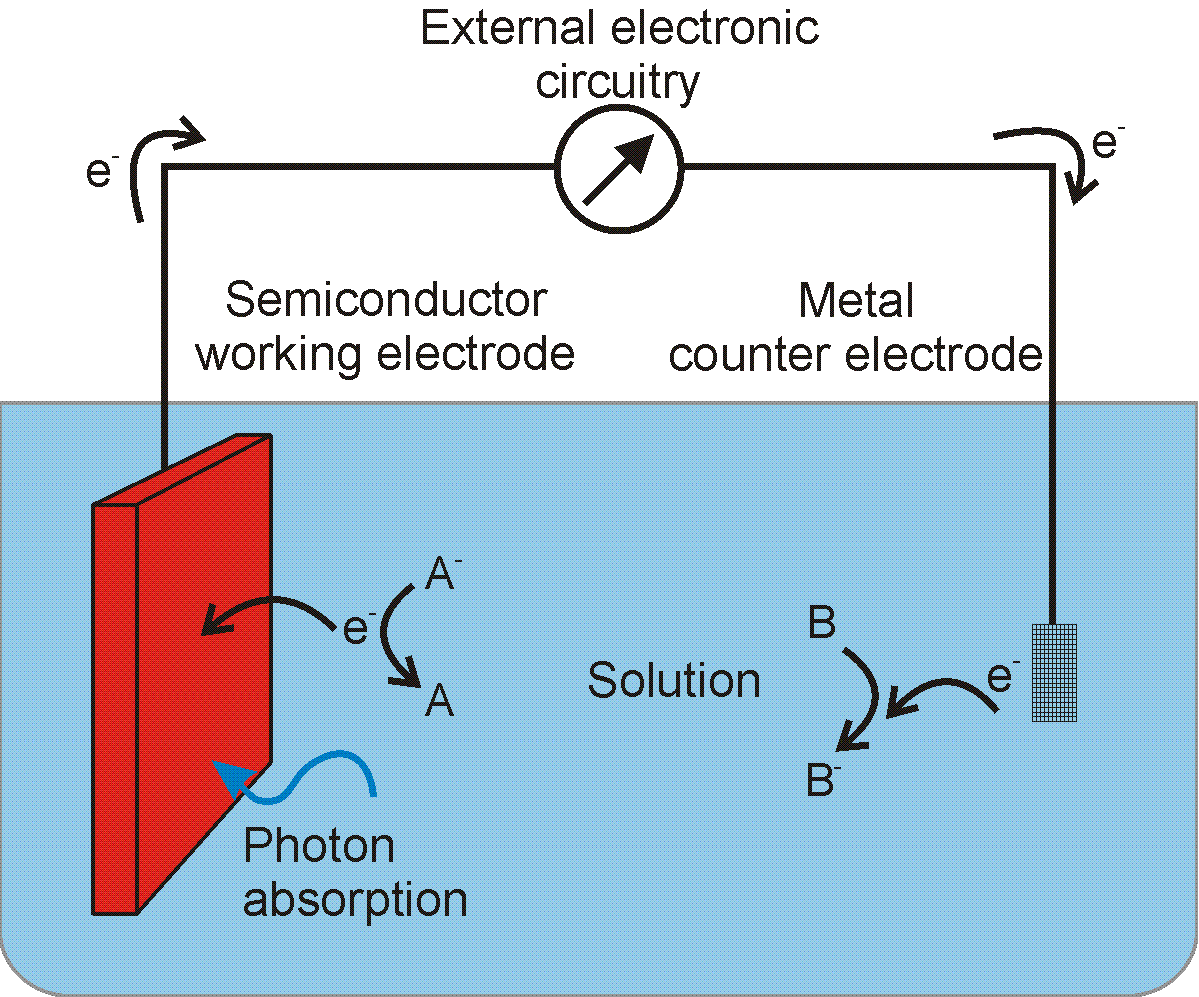

If the desired output of a photoelectrochemical cell is electricity, then one can use a reversible redox couple to harvest excited electrons or holes. Since the redox couple undergoes electron transfer without any associated chemical reaction, no energy is stored in the form of chemical fuels. It is common to refer to the redox couple as an electron shuttle in this case because it is acting as a carrier for the electron. No net change in the solution composition occurs because the reaction at the semiconductor electrode is the opposite reaction of that occurring at the counter electrode. This is illustrated in Figure 1 if redox couple �B� is replaced with redox couple �A�. For example, if an n-type semiconductor is immersed into a solution of ferrocene and ferrocenium (singly-oxidized ferrocene) and is illuminated, excited holes will be driven to the surface. A molecule of ferrocene that comes close to the surface can donate an electron to the electron poor semiconductor, being oxidized to ferrocenium in the process. If the semiconductor is connected to an external circuit that includes a load, then the excited electrons can exit the bulk of the semiconductor to do work on the load (for example, a light bulb). A metallic counter electrode that is also immersed in the solution and used to return the electrons from the external circuit to the ferrocenium in solution, reducing it back to ferrocene and closing the circuit. Thus, no net change in the solution composition occurs.

|

|

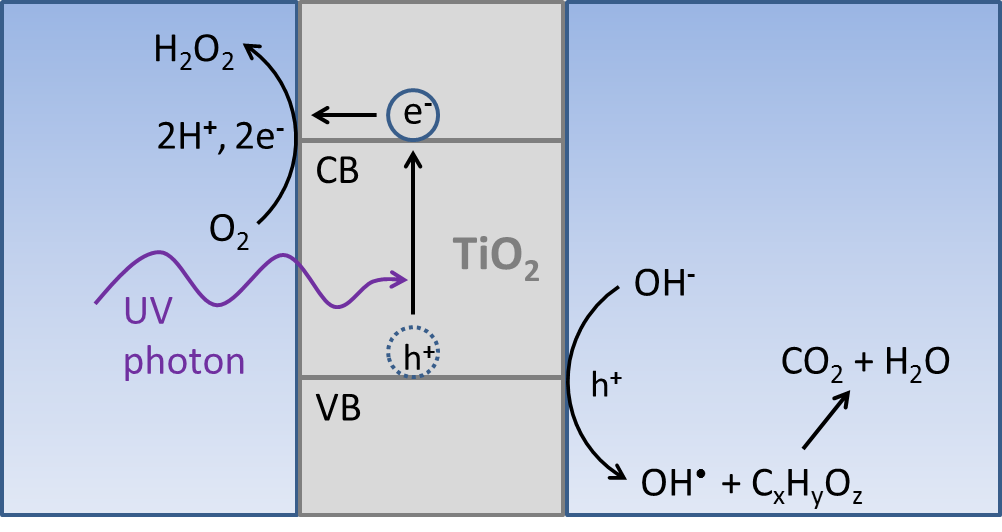

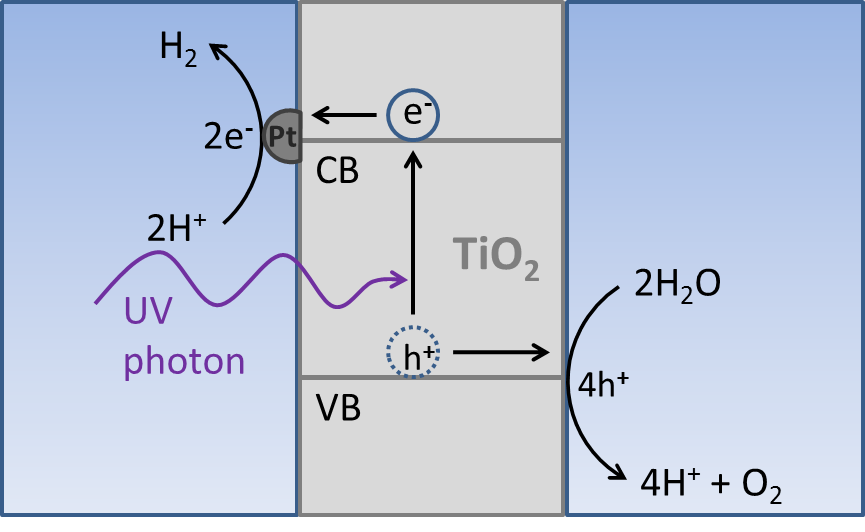

| Fig. 3 Diagram of a water splitting titanium dioxide photoelectrochemical cell. A titanium dioxide electrode immersed in deoxygenated water and coated with platinum catalyst particles will split water into its constituent elements upon irradiation with sunlight. Photoexcited electrons are consumed to generate hydrogen and holes are used to produce oxygen. |

Water

Water

Due ot its abundance and low cost, the most common choice of redox couple source is water. Both hydrogen and oxygen are gases at room temperature, which is advantageous in terms of separating the products from reactants. By using a strontium titanate electrode it is possible to use sunlight to drive water splitting redox reactions and thus store energy from the sun in the form of chemical fuel, as shown in Figure 3.

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide

Another abundant fuel precursor is carbon dioxide. By using the energy from excited (high energy) electrons generated in a semiconductor electrode in conjunction with appropriate catalysis, it is possible to reduce carbon dioxide can be reduced into several different products, depending on the conditions and the catalyst used. Some possible reduction products include methane, methanol, formate (formic acid), and carbon monoxide. Methane and methanol can both be directly used as fuels, while formate and carbon monoxide are important precursors to fuels as well as other industrial chemicals. For example, formic acid can be decomposed into hydrogen and carbon monoxide under heat with proper catalysis. Then with additional catalysis, this mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide (industrially referred to as synthesis gas) can be converted to a range of hydrocarbon fuels, ranging from methane to the longer chain hydrocarbons used in diesel fuel.

Use as a large scale energy conversion strategy, advantages and disadvantages

A photocatalytic cell, such as a titanium dioxide water purification system, is useful in its ability to generate reactive oxidizing species, but it has no potential for energy conversion because the net chemical reactions are energetically downhill. To make a significant impact on the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere that result from the consumption of fossil fuels, energy capture and storage on the scale of tens of terawatts (1 terawatt = 1012 watts, a million-million watts) is needed. Fortunately, the sun provides more than one hundred thousand TW over the surface of the earth. Unfortunately, sunlight is a transient resource, and a scheme for long term storage on the terawatt scale is needed. Any solar cell that produces electricity (such as a regenerative photoelectrochemical cell) suffers from this fundamental limitation.Currently, no cost effective way to store electrical energy exists on a global, industrial scale. Conventional batteries and capacitors do not have the capacity to store enough energy for nighttime power needs. Additionally, only a fraction of the energy needs of modern society can be supplied by electricity. Heating and transportation needs are much more easily and efficiently met by combustible fuels. However, most photoelectrochemical cells are vulnerable to corrosion due to the exposure of the semiconductor electrode to water. In contrast, standard solar cells are stable for decades, because they are sealed to protect the semiconductor from exposure to water.

A photosynthetic cell is distinct from a photocatalytic or regenerative cell in that it induces a net uphill energy change in one or more of the chemical species in solution. Thus, it is the only type of photoelectrochemical device that can store light energy directly in chemical bonds to produce a fuel. Nature uses photosynthesis to store light energy in the form of energy rich compounds, such as sugars, on a vast scale (all green plants and algae) so it should be possible, at least in principle, to mimic this process as a method of generating chemical fuels such as hydrogen or gasoline on an industrial scale. However, a living plant has a rather modest energy budget compared to that of a modern day human and plants have a small solar energy to biomass conversion efficiency averaging 0.5%, on a yearly basis. The fuel that plants produce in the form of sugars must be fermented into ethanol before it is of practical use as a fuel and yet further energy losses are incurred in this transformation.

Recently, a solar to fuel conversion efficiency of 12% has been demonstrated for a photosynthetic cell, splitting water to make hydrogen. However, this system used the expensive and rare semiconductors gallium arsenide and gallium indium phosphide, as well as platinum metal. Additionally, it was only stable for a matter of hours. In order to meet the energy demands of modern society on a large scale, additional research is needed to discover cheap and abundant semiconductor materials that are both stable in aqueous conditions and capable of absorbing a large portion of the solar light spectrum. Also, cheaper materials are needed to act as catalysts to maximize the efficiency of the conversion of the excited (high energy) electrons released by the semiconductor into fuel.

The gaseous nature of hydrogen presents a challenge for utilization as a transportation fuel. The energy density of compressed hydrogen gas (by volume) is only 1/6th that of gasoline. Methods for the compression or liquefaction of hydrogen are available, but they involve very low temperatures and large energy expenditures. Compressed hydrogen is difficult to store and there currently no infrastructure exists for transporting and distributing hydrogen as a fuel. Thus, hydrogen produced by solar power would most likely be reacted with carbon dioxide to form methanol, which is a liquid fuel and is thus much easier to transport and store. Additional energy is required to concentrate carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and react it with hydrogen but this could be less energy intensive than liquefying hydrogen directly.

Because modern society revolves around the use of hydrocarbon fuels, carbon dioxide reduction is an attractive alternative to water splitting. The direct production of liquid fuels such as methanol could be much more efficient in an integrated photoelectrochemical system than production of H2 as an intermediate step. An initial energy expenditure would be necessary to concentrate carbon dioxide from flue gas or from the atmosphere to achieve reasonable photosynthetic efficiencies. This process, however, would allow the burning of hydrocarbon fuels in a carbon neutral cycle, where the net release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is zero.

Summary

Photoelectrochemistry provides the potential to store light energy directly in the form of chemical bonds without involving electricity as an intermediate energy carrier. This approach presents an opportunity for efficiency increases in the conversion process and for a reduction in the overall process cost.Both carbon dioxide reduction and water splitting have the potential to provide clean and renewable energy. The challenge lies in finding cheap, abundant, and efficient light absorbers and catalysts and integrating them into a system that functions over many length scales.

Related article

Electrochemistry of plant life

Bibliography

- Principles of Semiconductor Devices, B. Van Zeghbroeck, 2011.

http://ecee.colorado.edu/~bart/book/book/title.htm

- Solar Cell Device Physics (2nd edition), S. J. Fonash, Academic Press/Elsevier, Burlington, MA, 2010.

- Nanostructured and Photoelectrochemical Systems for Solar Photon Conversion, M. D. Archer and A. J. Nozik (editors), Imperial College Press, London, 2008.

- Physics of Semiconductor Devices, S. M. Sze and K. K. Ng, Wiley-Interscience,

Hoboken, NJ, 2007.

- Toward Cost Effective Solar Energy Use, N. S. Lewis, �Science� Volume 315, pp 798-801, 2007.

- Semiconductors, H. F�ll, Kiel, Germany, 2007.

http://www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/semi_en/index.html

- Powering the Planet: Chemical Challenges in Solar Energy Utilization, N. S. Lewis and D. G. Nocera, �Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA� Volume 103, pp 15729-15735, 2006.

- Beyond Oil and Gas: The Methanol Economy, G. A. Olah, A. Goeppert, and G. K. S. Prakash, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, 2006.

- Semiconductor Devices: Physics and Technology (2nd edition),

S. M. Sze, Wiley, New York, 2001.

- Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications (2nd edition), A. J. Bard and L. R. Faulkner, Wiley, New York, 2001.

- TiO2 Photocatalysis: Fundaments and Applications, A. Fujishima, K. Hashimoto, and T. Watanabe, BKC, Tokyo, Japan, 1999.

- Semiconductor Device Fundamentals, R. F. Pierret, Addison Wesley, Reading, MA, 1996.

- Principles and Applications of Semiconductor Photoelectrochemistry, M. X. Tan, P. E. Laibinis, S. T. Nguyen, J. M. Kesselman, C. E. Stanton, and N. S. Lewis, in �Progress in Inorganic Chemistry� Volume 41, Chapter 2, pp 21-144, K. D. Karlin (editor), Wiley, New York, 1994.

- Photoeffects at the Semiconductor/Liquid Interface, N. S. Lewis, �Annual Review of Materials Research� Volume 14, pp 95-117, Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, CA, 1984.

- Fundamentals of Solar Cells: Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conversion, A. L. Fahrenbruch and R. H. Bube, Academic Press, New York, 1983.

- M�moire sur les Effets �lectriques Produits Sous l'Influence des Rayons Solaires, E. Becquerel, �Comptes Rendu des S�ances de l'Acad�mie des Sciences, Paris� Volume 9, pp 561�567, 1839. Available on the WWW.

Return to: Top – Encyclopedia Home Page – Table of Contents – Author Index – Subject Index – Search – Dictionary – ESTIR Home Page – ECS Home Page

ECS | Redcat Blog | ECS Digital Library