Return to:

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

ELECTROACTIVE POLYMERS (EAP)

Yoseph Bar-Cohen

JPL/Caltech (MS 67-119)

4800 Oak Grove Drive

Pasadena, CA 91109-8099, USA

E-mail: yosi@jpl.nasa.gov

WWW Home Page:

http://ndeaa.jpl.nasa.gov

(December, 2004)

|

Actuators are driving many mechanisms that are use in our daily life. Increasingly, there are efforts to reduce their size, mass, and power as well as use them to operate biologically inspired devices. Electroactive ceramic actuators (for example, piezoelectric and electrostrictive) are effective, compact actuation materials and they are used to replace electromagnetic motors. However, while these materials are capable of delivering large forces, they produce a relatively small displacement on the order of magnitude of fraction of a percent. For many years, it has been known that certain types of polymers can change shape in response to electrical stimulation, however, initially these materials produced only a relatively small strain (stretching, contracting, or bending). Since the beginning of the 1990s, new electroactive polymer (EAP) materials have emerged that exhibit large strains and they led to a great paradigm change with regards to their capability. The unique properties of these materials are highly attractive for biomimetic applications such as biologically inspired intelligent robots. Increasingly, engineers are able to develop EAP actuated mechanisms that were previously imaginable only in science fiction.

In 1999, in recognition of the need for international cooperation among the developers, users, and potential sponsors, the author initiated a related annual SPIE (Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers, The International Society for Optical Engineering) conference as part of the Smart Structures and Materials Symposium. This SPIE EAP Actuators and Devices (EAPAD) conference was held in Newport Beach, California, USA and was the largest ever on this subject, marking an important milestone and turning the spotlight onto these emerging materials and their potential. The EAPAD conferences are now organized annually and have been steadily growing in number of presentations and attendees. The author is also issuing electronically the semi-annual WW-EAP Newsletter, and mentoring a website that archives related information and includes links to homepages of EAP research and development facilities worldwide [http://eap.jpl.nasa.gov]. In the past few years, in addition to the SPIE conferences, several other conferences and special sessions within conferences focusing on electroactive polymer actuators have also taken place.

History and currently available mechanical active polymers

Polymers that can be activated to change shape or size have been available for many years. The activation mechanisms include chemical, thermal, pneumatic, optical, and magnetic. The convenience and practicality of electrical stimulation, and technology progress led to a growing interest in EAP materials. The first documented experiment with EAP materials is attributed to Roentgen where in 1880 he observed length change in a rubber-band (with one fixed end and a mass attached to the free end) that he subjected to electric field. The next milestone was recorded in 1925 with the discovery of a piezoelectric polymer, called "electret", when carnauba wax, rosin, and beeswax were solidified by cooling while subjected to a dc electric field. The strain and work output of electrets is too low to be applicable as actuators and therefore their use has been limited to sensors. Following the 1969 observation of a substantial piezoelectric activity in polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), investigators started to examine other polymer systems, and a number of effective materials were developed. The largest progress in EAP materials development has been reported in the last fifteen years where materials that can create linear strains that can reach up to 380% have been developed.

Generally, EAP can be divided into two major groups based on their activation mechanism including: ionic (involving mobility or diffusion of ions) and electronic (driven by electric field). A list of the leading EAP materials is given in Table I and a summary of the advantages and disadvantages of these two groups of materials is given in Table II.

|

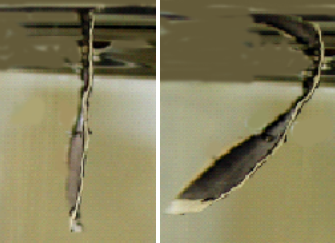

| Fig. 1. Conductive EAP actuator (left) activated by 2 V and 50 mA is shown bending (right). |

| Table I. List of the leading EAP materials |

|---|

| Electronic EAP | Ionic EAP |

|

|

The electronic polymers (electrostrictive, electrostatic, piezoelectric, and ferroelectric) are driven by electric fields and can be made to hold the induced displacement under activation of a dc voltage, allowing them to be considered for robotic applications. Also, these materials have a greater mechanical energy density and they can be operated in air with no major constraints. However, they require a high activation field (>100 MV/meter) close to the breakdown level. In contrast, ionic EAP materials (gels, polymer-metal composites, conductive polymers, and carbon nanotubes.) are driven by diffusion of ions and they require an electrolyte for the actuation mechanism. Their major advantage is the requirement for drive voltages as low as 1 to 2 volts. However, there is a need to maintain their wetness, and except for conductive polymers and carbon nanotubes it is difficult to sustain dc-induced displacements. The induced displacement of both the electronic and ionic EAP can be geometrically designed to bend, stretch, or contract. Any of the existing EAP materials can be made to bend with a significant curving response, offering actuators with an easy to see reaction and an appealing response. However, bending actuators have relatively limited applications due to the low force or torque that can be induced.

| Table II. Summary of the advantages and disadvantages of the two basic EAP groups |

|---|

| EAP type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Electronic EAP |

- Exhibit rapid response (milliseconds)

- Can hold strain under dc activation

- Induces relatively large actuation forces

- Exhibits high mechanical energy density

- Can operate for a long time in room conditions

|

- Requires high voltages (~100 MV/meter). Recent development allowed for (~20 MV/meter) in the Ferroelectric EAP

- Independent of the voltage polarity, it produces mostly monopolar actuation due to associated electrostriction effect.

|

| Ionic EAP |

- Natural bi-directional actuation that depends on the voltage polarity.

- Requires low voltage

- Some ionic EAP like gonductive polymers have a unique capability of bi-stability

|

- Requires using an electrolyte

- Require encapsulation or protective layer in order to operate in open air conditions

- Low electromechanical coupling efficiency

- Except for CPs and NTs, ionic EAPs do not hold strain under dc voltage

- Slow response (fraction of a second)

- Bending EAPs induce a relatively low actuation force

- Electrolysis occurs in aqueous systems at >1.23 V

|

EAP materials are still custom made mostly by researchers and they are not available commercially. To help in making them widely available, the author established a website that provides fabrication procedures for making the leading types of EAP materials [http://ndeaa.jpl.nasa.gov/nasa-nde/lommas/eap/EAP-recipe.htm]. To help further, the author compiled inputs from companies that make EAP materials, and prototype devices or provide EAP related processes and services. The input was documented in a handy table that is posted on a link to the WW-EAP website [http://ndeaa.jpl.nasa.gov/nasa-nde/lommas/eap/EAP-material-n-products.htm].

|

| Fig. 2. An artistic interpretation of the Grand Challenge for EAP actuated robotics. |

Unfortunately, the materials that have been developed so far are still exhibiting low conversion efficiency, are not robust, and there are no standard commercial materials available for consideration in practical applications. In order to be able to take these materials from the development phase to application as effective actuators, there is a need to establish an adequate EAP infrastructure. Effectively addressing the requirements of the EAP infrastructure involves developing adequate understanding of EAP materials' behavior, as well as processing and characterization techniques. Improved collaboration among developers, users, and sponsors as well as increased resources with a growing number of investigators led to rapid progress in the field.

At the opening of the first EAPAD Conference in 1999, in an effort to promote worldwide development towards the realization of the potential of EAP materials, the author posed an armwrestling challenge to the worldwide engineers. A graphic rendering of this challenge is illustrated in Figure 2 and it is intended to use the human arm as a baseline for the implementation of the advances in the development of EAP materials. Success in wrestling against humans will enable biomimetic capabilities that are currently considered impossible. It would allow applying EAP materials to improve many aspects of our life where some of the possibilities include smart implants and prosthetics, active clothing, and realistic biologically-inspired robots. Recent advances in understanding the behavior of EAP materials and the improvement of their efficiency led to the important milestone that the first competition is being planned for March 2005.

EAP characterization

An important aspect of the development of EAP materials is the establishment of effective characterization methods. These methods are needed to make measurements of the properties with minimum effect on the material and thus allow obtaining accurate and detailed information. The obtained information is critical to designers who are considering construction of EAP based mechanisms and assess their competitive capability. Studies are currently underway to define a unified matrix and establish effective test capabilities. While the electro-mechanical properties of the electronic-type EAP materials can be addressed with some of the conventional test methods, ionic-type EAP materials (for example, IPMC) are posing technical challenges. The response of these materials is complex and is associated with mobility of cation on the microscopic level with a strong dependence on the moisture content and they have a hysteretic behavior. The use of a video camera and image processing software offers a capability to study the deformation of ionic type EAP strips under various mechanical loads. Simultaneously, the electrical properties and the response to electrical activation can be measured. Nonlinear behavior has been clearly identified in both the mechanical and electrical properties and efforts are made to model this behavior.

Applications of EAP

EAP materials have properties that make them very attractive for many biomimetic applications. As polymers, EAP can be easily formed in various shapes and their properties can be engineered. Unfortunately, the materials that have been developed so far are still exhibiting low conversion efficiency, are not robust, and there are no standard commercial materials available for consideration in practical applications.

|

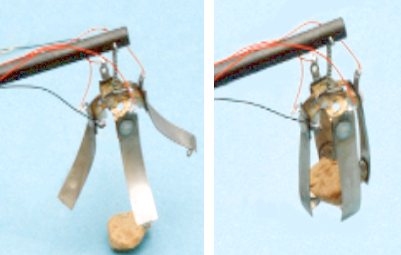

| Fig. 3. A gripper with four EAP fingers lifting a rock. |

In recent years, there has been significant progress in the field of EAP toward making practical actuators, and commercial products are starting to emerge. The first milestone product was announced by Eamax, Japan, at the end of 2002, and it is a biomimetic device in the form of a fish robot [http://www.eamex.co.jp/video/fish.wmv]. Moreover, a growing number of organizations are exploring potential applications for EAP materials, and cooperation across many disciplines is helping to overcome the related challenges. The mechanisms and devices that are being considered or developed are applicable to aerospace, automotive, medical, robotics, exoskeletons, articulation mechanisms, entertainment, animation, toys, clothing, haptic and tactile interfaces, noise control, transducers, power generators, and smart structures.

To mimic a biological hand using simple elements, the author and his coinvestigators constructed a miniature robotic arm that was lifted by a rolled dielectric elastomer EAP as a linear actuator and four Ionic Polymer Metallic Composite (IPMC)-based fingers as a bending actuator. The linear actuator was used to raise and drop a graphite/epoxy rod which served as a simplistic representation of a robotic arm. Upon activating the actuator, the arm sustains a series of oscillations that need to be dampened for accurate positioning. This requires sensors and a feedback loop to support the kinematics of the system control. Several alternatives were explored, including establishment of a self-sensing capability, but more work is needed before such an arm can become practical. To produce an end-effector for the arm, a four finger gripper was developed (see Figure 3). These bending actuator fingers were made of IPMC strips with hooks at the bottom emulating fingernails. As shown in Figure 3, this gripper grabs rocks very similar to the human hand.

Summary

Recent progress in the field of electroactive polymers (EAP) led to the development of materials that exhibit large displacement in response to electrical stimulation. For their operational similarity to biological muscles, this capability is making EAP materials attractive as actuators, particularly for their resilience, damage tolerance, and ability to induce large actuation strains (stretching, contracting, or bending). The application of these materials as actuators to drive various manipulation, mobility, and robotic devices involves multi-disciplines including materials, chemistry, electromechanics, computers, and electronics. Even though the actuation force of existing EAP materials and their reliability require further improvement, there has already been a series of reported successes in developing EAP-actuated mechanisms including a fish-robot, catheter-steering element, miniature manipulator and miniature gripper, and dust wiper. Some of the considered applications are still far from being practical, and it is important to tailor the requirements to the level that current materials can address. Using EAP to replace existing actuators may be a difficult challenge and therefore it is highly desirable to identify a niche application where EAP materials would not need to compete with existing technologies.

In order to exploit the highest benefits from EAP, multidisciplinary international cooperative efforts need to grow further among scientists, engineers, and other experts (for example, medical doctors, etc.). Experts in chemistry, materials science, electro-mechanics/robotics, computer science, electronics, etc., need to advance the understanding of the material behavior, as well as develop EAP materials with enhanced performance, processing techniques and applications. Effective feedback sensors and control algorithms are needed to address the unique and challenging aspects of EAP actuators. If EAP-driven artificial muscles can be implanted into a human body, this technology can make a tremendously positive impact on many human lives.

The field of EAP is far from mature but progress led several research labs to consider making EAP actuated robotic arms for armwrestling with a human opponent. A robot win will demonstrate that EAP performance has reached a level, at which devices can be designed to emulate physical functions that human performs.

Acknowledgement

Some of the research reported in this manuscript was conducted at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), California Institute of Technology, under a contract with National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

Related article

Conducting polymers

Further reading

Bibliography

- Electroactive Polymer (EAP) Actuators as Artificial Muscles - Reality, Potential and Challenges (2nd edition), Y. Bar-Cohen (editor), Vol. PM136, SPIE Press, Bellingham, WA 2004.

- Biologically-Inspired Intelligent Robots, Y. Bar-Cohen and C. Breazeal (editors), Vol. PM122, SPIE Press, Bellingham, WA 2003.

- Proceedings of the first SPIE's Electroactive Polymer Actuators and Devices (EAPAD) Conference, Smart Structures and Materials 1999, Y. Bar-Cohen (editor), SPIE Proceedings Series Vol. 3669, SPIE Press, Bellingham, WA 1999.

- Giant electrostriction and relaxor ferroelectric behavior in electron-irradiated poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluorethylene) copolymer, Q. M. Zhang, V. Bharti, and X. Zhao, "Science" Vol. 280, pp 2101-2104, 1998.

- Direct observation of abrupt shape transition in ferrogels induced by nonuniform magnetic field, M. Zrinyi, L. Barsi, D. Szabo, and H. G. Kilian, "Journal of Chemical Physics" Vol. 106, pp 5685-5692, 1997.

- Dressware: wearable piezo- and thermo-resistive fabrics for ergonomics and rehabilitation, D. de Rossi, A. Della Santa, and A. Mazzoldi, in "Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference IEEE, Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 1997" Vol. 5, pp 1880-1883, IEEE, Chicago, IL 1997.

http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/abs_free.jsp?arNumber=758700

- Polymer Piezoelectric Transducers For Ultrasonic NDE, Y. Bar-Cohen, T. Xue, and S.-S., Lih, in "1st International Internet Workshop on Ultrasonic NDE, Subject: Transducers", UTonline Journal (NDTnet), Vol. 11, No. 9, September, 1996.

http://www.ndt.net/article/yosi/yosi.htm

- A new model for electrochemical oxidation of polypyrrole under conformational relaxation control, T. F.Otero, H. Grande, and J. Rodriguez, "Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry" Vol. 394, pp 211-216, 1995.

- Static and Dynamic Characteristics of McKibben Pneumatic Artificial Muscles, C. P. Chou and B. Hannaford, in "Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation" San Diego, CA, pp 281-286, 1994.

http://brl.ee.washington.edu/Publications/Publications_html/Rep077.html

- Light-Sensitive Polymers, G. Van der Veen and W. Prins, "Nature, Physical Science" Vol. 230, pp 70-72, 1971.

- Rapid Swelling and Deswelling of Reversible Gels of Polymeric Acids by Ionization, A. Katchalsky, "Experientia" Vol. 5, pp 319-320, 1949.

- On the Permanent Electret, M. Eguchi, "Philosophical Magazine" Vol. 49, pp 178, 1925.

Listings of electrochemistry books, review chapters, proceedings volumes, and full text of some historical publications are also available in the Electrochemistry Science and Technology Information Resource (ESTIR). (http://knowledge.electrochem.org/estir/)

Return to:

Top –

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

|