Return to:

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

JULIUS TAFEL - HIS LIFE AND SCIENCE

Klaus Muller

Wendelsteinstrasse 18

D-85560 Ebersberg, Germany

(April, 2007)

|

| Fig. 1. Professor Julius Tafel, around 1905. (Courtesy Chemical Institute, Wurzburg University) |

Tafel's name is an adjective in the language of all trained electrochemists, yet not too many of them would even know his first name. The fame of the Tafel law and Tafel line overshadow Tafel's claim to fame as one of the founders of modern electrochemistry.

His origins

Julius Tafel was born on the 2nd of June 1862 in Choindez, a community today part of the Swiss Canton of Jura, at the German-French language border. In 1862 it was the location of the most remote of Von Roll's developing iron and steel works. Tafel's father, Julius Tafel (1827-1893), from a Wurttemberg family in Stuttgart, who had studied chemistry in Tubingen, had became a director of the Choindez works in 1856, from where he moved on to a top management position in the Gerlafingen steel works in 1863 (in the Swiss canton of Solothurn). He went back to Germany with his family in 1875, to found and head the "J. Tafel & Co." steel rolling mills of Nuremberg that existed until 1975. The Julius Tafel Hall is now the center piece of the Nuremberg Industrial Arts Museum.

His training, sphere, and early work

Julius junior attended the Realgymnasium (junior college with scientific orientation) in Stuttgart and Nuremberg, and from 1880 studied chemistry in Zurich, Munich, and Erlangen. Emil Fischer had become a professor in Erlangen in 1882, and Tafel received his Ph.D. under Fischer in 1884, followed Fischer to Wurzburg in 1885 as private assistant, and produced his Habilitationsschrift ("super Ph.D.") in 1888.

In Fischer's (very simple) private laboratory, Tafel was chief among those working with Fischer on carbohydrate synthesis in the 1880's (Fischer was the 1902

Chemistry Nobel Prize winner). Tafel handled the experimental demonstrations when Fischer first reported about this work to the German Chemische Gesellschaft in Berlin in 1890.

When Fischer moved on to Berlin in 1892, Tafel remained in Wurzburg, a very distinguished university of the time and having many connections to electrochemistry. Hantzsch then had the chair from 1893 to 1903, and Tafel held it from 1903 until 1910. He was succeeded by Buchner (who was the 1907

Chemistry Nobel Prize winner for his work on fermentation). In the neighboring physics laboratories, the chairs were held in succession by Kohlrausch, Roentgen (the first ever Nobel Prize winner of Physics in 1901), Wien (1911

Physics Nobel Prize), and Harms. Fick was professor of physiology (until 1899).

After 1892, Tafel's scientific interest centered on strychnine (a very well known strong poison), purines, and a variety of amino compounds. The laboratory facilities were simple, and Tafel's important health problems, including a chronical phenylhydrazine poisoning, may safely be attributed to poor venting. Tafel's work and methods turned increasingly toward physical and electrochemistry. After time as a guest of Ostwald in Leipzig, he landed the coup - in 1898 - of reducing strychnine electrochemically at lead cathodes. Nobody had succeeded in this reduction by chemical means. Electrolytically at lead, one and both oxygen atoms could be replaced by hydrogen atoms. In this way Tafel could show that the two oxygen containing rings were acting in the same sense, to make the molecule so highly poisonous. Uric acid reduction was another absolute first in 1901.

1898: Professor Tafel

Until 1893, Tafel had lectured organic chemistry, but after 1893 he lectured physical and general chemistry. By German tradition, this would include lots of electrochemistry, and lots of experimentation. With strychnine reduction, Tafel had truly turned electrochemist. His activities and life took on a new rhythm. He was named a professor in 1898, became extraordinarius in 1902, and a husband, ordinarius, and director of the institute in 1903.

A careful observer, Tafel soon was able to summarize his major and rather far-reaching general deductions from his experimental work. One can read up on this in an invited review paper in Zeitschrift fur Elektrochemie in 1906. The main points were published already in 1900, and constitute the foundations of electrocatalysis.

- Use of a hydrogen coulometer in series with the electrolytic cell, in order to deduce from the amounts of hydrogen evolved in the chief reaction vessel and in the coulometer whether an electrochemical reaction actually took place. The importance of this is: recognition of the factor of time in reactions (the birth of kinetics), recognition of the factor of yield when working with hard-to-reduce substances. With these findings, Tafel was well ahead of his time. Tafel also would not call the substance being reduced a depolarizer, as was customary then (and even now): for Tafel, reduction was a competitive act (competition between two reduction reactions) - with the corresponding relative yields of the two reactions.

- Watching out for the effect of impurities showed that lead and mercury (or cadmium) are needed as cathodes for the reduction of hard-to-reduce substances, but

- traces of foreign metals have to be excluded from the cathode compartment of the electrolytic cell in order to obtain reproducible results - they could come from impure lead samples, impure chemicals, and materials dissolving from the anode, and these impurities could deposit on the surface of the cathode

- added traces of platinum halted reduction on lead completely (Tafel calculated that these traces resulted in a 0.2-nm layer of platinum deposited on the cathode surface - we now call this submonolayer coverage)

- special-quality lead is needed for organic preparative work with electrochemical methods.

All these effects would later be coined catalytic poisoning.

- Observing the anode during work on cathodic reduction, Tafel found that even platinum is not inert as an anode: it readily dissolves - in contrast to what Caspari (1989), of Nernst's school, had claimed. It is safe to say that Tafel's observation went unheeded for many decades and well into the space age, fouling up results of research into alternative electrocatalysts. In Tafel's words: "Use of platinum anodes, therefore, represents great danger in all work involving polarization" since the cathodes become "verseucht" ("infested"). This was 1905 - more than 100 years ago.

- In their disturbing effects on electrolytic reduction of hard-to-reduce substances at lead, the order of metals is: platinum > silver > tin > copper > mercury > zinc > iron, according to Tafel's early work in 1900. Adding a lead salt during the run could alleviate smaller perturbations, as the cathodic lead deposit that forms would cover the contaminant. If the solution was more seriously contaminated, Tafel recommended changing the cathode, but taking it out of the solution without interrupting the current - that's what many decades later would be stressed as pre-electrolysis.

- For preparing a more productive lead cathode, Tafel (1900) recommended an anodic pretreatment (covering the lead with lead superoxide), followed by cathodic treatment, so as to obtain a spongy, active surface - a cathode pretreatment far safer and more convenient than by chemical means. Cathodes with a more highly developed surface area were less sensitive to contaminants, and more productive in the desired reduction reaction.

- How to determine the overpotential (for the hydrogen evolution) of a metal that everybody was talking about?

- Set up a cell with a given cathode and a sufficiently well oxidized lead anode.

- Pass a given current, note the steady potential difference being attained.

- Add platinum solution to the cathode compartment, so that the cathode becomes platinum-covered.

- Set the current back to the former value, note the new steady potential difference being attained.

- The given cathode's overpotential (relative to platinum) is then known from the difference between the two potential differences (assuming that the platinized cathode has the same overpotential as platinum itself).

- Practical implication: A reduction of an organic substance will only be successful when the cathode's hydrogen overpotential attains or surpasses a certain value. This is because these are competitive reactions and if the overpotential for hydrogen evolution is lower than that for the reduction of the organic substance, the hydrogen evolution will dominate (see the Appendix). According to Caspari (of the Nernst school), lead and mercury exhibit the highest hydrogen overpotentials. It was Tafel who recognized how to make use of this phenomenon; C. F. Boehringer (Mannheim) filed patents on this basis in 1902.

Thus, in the 1900 paper of Tafel we have the basic elements of modern views on electrocatalysis, surface preparation, effect of impurities, pre-electrolysis, and the qualitative and quantitative aspects of electrochemical kinetic research.

The Tafel law

It may not be an accident that Tafel completely abstained from using the term depolarizer, so much used then and sometimes even now. Certainly a nitro compound in acidic solution at platinum could look like one - but not so strychnine and caffeine at whatever electrode! A "depolarizer" should be seen as an electrode reactant which imposes its own electrochemical behavior as the potential-determining event. Depolarizer effects require a good measure of reversibility (fast reaction kinetics!) of the reaction involved. In those days, a depolarizer was a substance that reduced the electrode potential when added to the solution, it was sometimes overlooked that the depolarizer completely changed the electrode reaction, it was itself reacting because its reaction had a smaller overpotential than that of the original reaction taking place without the presence of the depolarizer.

At around 1900, the stress on reversible situations had prevented

Nernst (the 1920

Chemistry Nobel Prize winner) and coworkers from recognizing the catalytic aspects, the effects of the cathode material, the nature of the effect of electrode potential. That's why there is a Nernst equation, reflecting potential-determining reactivity at an electrode, and a Tafel equation - worlds apart and reflecting the effect of imposed electrode potential on resulting reaction rates (current density). The Nernst equation is applicable in equilibrium situations when there is no current flowing through the cell, while the Tafel equation is applicable to situations with current flowing (nonequilibrium conditions).

When the German Electrochemical Society met in Wurzburg in 1902, Tafel was able to provide preliminaries on his experimental inquiries into this topic to the distinguished assembly, but only in 1905 then, an entire issue of the Zeitschrift fur physikalische Chemie was filled with his two papers (112 pages) on overpotential and the reduction of organic compounds, setting forth the famous law. An invited review paper provided summary in 1906.

For mercury cathodes and (approximately) for lead and cadmium cathodes, Tafel found the law:

η = a + b×log i η = a + b×log i

where �η� is the polarization, �a� and �b� are constants (b = 0.107 for hydrogen evolution in aqueous solution at metals, the value increasing with temperature), and �i� is the current density. Tafel reported measured data for a wide range of materials and provided ample discussion. He argued that Tafel law was not an obvious consequence of the Nernst equation.

In this way for the first time, electrode kinetics appeared separate from energetics; and made it possible to systematically study irreversible reactions. Electrode reactions started to be emancipated from Nernst's electrode potential. In Nernst, a potential is the result of ionic concentrations coexisting at the electrode; in Tafel, an applied potential, or in this context rather: overpotential (or applied potential difference), becomes a driving force for reactions changing these concentrations.

|

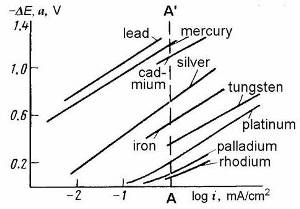

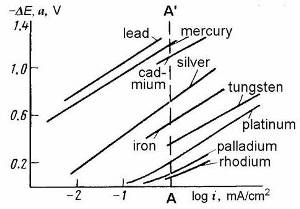

| Fig. 2. Polarization curves for hydrogen evolution at a number of metals in acidic solutions. Line AA' is drawn at �i� = 1 mA/cm2 as the conventional reference current density for reporting values of �a�. It can be seen that the Tafel law holds for most of these plots. |

The empirical equation of the Tafel law is that of a straight-line logarithmic plot if �a� and �b� are constants, see Figure 2. From more complete theoretical equations based on simple mechanisms and kinetic behavior, Tafel law can be derived as a limiting case of a more complete and complex electrode kinetics equation (the Butler-Volmer equation) that holds above a certain value of overpotential. It holds for many metals and many simple reactions. Below said overpotential, the reverse reaction starts to become important and causes nonlinearity. This onset of nonlinearity is seen in a few of the lines plotted in Figure 2.

Nonlinearity may also arise when �η� varies with �i� for incidental reasons such as changes in the state of the electrode or changes in diffusion conditions. If such changes can be ruled out, then the Tafel plot (or Tafel line) and associated values of the constants will admit some kinetic and mechanistic interpretation. Constant �a� can be reformulated in terms of some "standard current density", �io�, usually termed an exchange current density, and is related to the reaction rate constants. Constant �b� (the Tafel slope) is the key connection to reaction rate theory, its chief virtue being that the overpotential, as the driving force, becomes related to the rate (the current density) of the "driven" reaction - that is, an electrode reaction driven at finite and interesting (useful) rates. With the use of modern rate theories, theoretically derived values of �b� can be compared to the measured value to test proposed reaction mechanisms.

Complications arise because, actually, signs must be applied in the equation of Tafel law above, and evidently should differ between anodic and cathodic directions. So, rigorously, the plus sign should be replaced by � (for anodic and cathodic overpotentials, respectively) and �i� should be replaced by �|i|� (the absolute value of �i�). The nonlinearity at low values of overpotential (say, below values of 50 to 100 mV) is caused by the influence of the reverse reaction. In simple cases, a reaction can be driven in either direction, from high cathodic current densities through "zero" all the way to high anodic current densities. "Zero" here implies, not the absence of reaction but the absence of net reaction, where at the electrode, the cathodic and anodic reactions occur at equal rates in opposite directions.

Tafel, incidentally, had no success in deriving the numerical value of �b� from theory (that is, from the Tafel mechanism, see the Appendix): the cathode potential on mercury and lead was found to increase much faster with current density than it should. On the other hand, ever since, the Tafel law was found to hold for many reactions, and at many more than the metals envisaged for the law by Tafel.

Tafel spelled out first that the definition of overpotential is only meaningful when a current density is indicated. (Implicitly: overpotential is a function, not a fixed value!) Overpotentials in Tafel's definition would be referred to the reversible hydrogen electrode. Making it a function of current density, he turned attention to electrode reactions as a rate process, such as would be discussed so much later, say, in the famous Horiuti and Polanyi paper of 1935.

In practical terms, for metals such as lead, cadmium, silver, and copper, Tafel observed states of "activation" and "depression" that depend on the electrode's polarization history, anolyte interference, chemical factors, and time factors - certainly, in our more modern view, the obvious effects of changes in the electrode's surface state.

In the 1905 papers, a table of overpotential values was given; it became a classical reference. In connection with his careful observations, Tafel discovered:

- catalysis takes place, not only with respect to the hydrogen reaction but also with respect to the reactions of organic substances

- hydrogen evolution and the reduction reactions occurring at the cathode are coordinated, irreversible reactions

- electrolytic reduction effects of a given cathode material may differ, not only quantitatively but also qualitatively from chemical reduction effects of the same material. For instance, ammonia is produced by reduction of nitric acid at copper cathodes, but hydroxylamine is produced at mercury cathodes (1902). ("Therefore, one must speak of a specific reduction effect of a given cathode" - electrocatalysis defined, if not named!)

- cathodic overpotential exists due to differences (between various metals) in the rate of hydrogen gas formation

- cathodes with the smallest overpotential accelerate hydrogen evolution most strongly

- the phenomenon of overpotential resides in the surface layer

- even a hydride layer will strongly affect catalysis

- "at high current densities one also gains the advantage of stirring by hydrogen evolution, an effect not produced by any other means of stirring to the same extent" (1906) - a most remarkable feature rediscovered so much later in the heyday of electroorganic synthesis!

While the �Tafel Law� was certainly his most lasting and even today very widely known and used contribution to science, he also made many other contributions, some of which are described briefly in the Appendix.

The last years

By the time of these discoveries, Tafel had already been forced into early retirement on account of failing health. From 1910 in Munich, he continued helping his pupils and became an eminent book reviewer. The reviews reveal a physical chemist embracing the modern concepts with critical statements regretting a lack of consideration for the theory of reaction rate and chemical equilibrium, the disregard of the phenomena of passivity, the narrow attention to nitro compounds in electrochemical work.

Aggravating illness, increasing insomnia, the realization that he would not be able to finish a projected modern text of organic chemistry, fear of a complete nervous breakdown led to death by his own hand on 2nd of September 1918. His wife Fanny died in Munich in 1968, at the age of 98.

Appendix

The Tafel mechanism The Tafel mechanism

Organic electrochemistry goes back to Faraday (formation of hydrocarbons during fatty acid electrolysis, 1834). By 1900 it was widely recognized that platinum was successful as a strongly oxidizing anode (though its benefits were more important for inorganic preparations such as peroxo compounds). A great many reduction reactions were known by 1900, but most workers studied easy-to-reduce substances at "inert" platinum - and overlooked kinetics, catalysis, the problems of yields. They also overlooked the highly different behavior of different cathode materials. It was the organic chemist Tafel who studied hard-to-reduce substances, say, caffeine in an aqueous solution:

[1]  C8H10O2N4 + 4H+ + 4e- = C8H12ON4 + H2O C8H10O2N4 + 4H+ + 4e- = C8H12ON4 + H2O

He recognized that a high overpotential for hydrogen evolution was the prerequisite for succeeding in such reductions, and inquired why. Only metals such as lead (highly pure, in the absence of impurities anywhere in the system, and not having a platinum anode as the counterelectrode) could be used. At any cathode, a reaction like [1] will compete with hydrogen evolution (H+ is a hydrogen ion in the solution):

[2]  2H+ + 2e- = H2 2H+ + 2e- = H2

According to Tafel (1900-1906), [1] may proceed with a measurable rate, only when [2] is sufficiently repressed (slow), "�therefore, overpotential values in a given solvent for [2] are a direct measure of the probability of [1] relative to [2], even if nothing is known about the reaction rate of [1]".

Why could [2] be slow? According to Tafel: "Probably, [2] is a composite reaction of

[2a]  2H+ + 2e- = 2H 2H+ + 2e- = 2H

and

[2b]  2H = H2 2H = H2

It should be assumed that the existence of �cathodic overpotential', qualitatively and quantitatively, is connected with the combination of 2H to H2, and this in fact because of a different catalytic action of metals on this process, which in the case of platinum is particularly strong."

This mechanism: reaction [2a], hydrogen ion reduction to atomic hydrogen adsorbed on the electrode surface, followed by reaction [2b], hydrogen atom recombination to molecular hydrogen on the electrode surface, is the famous Tafel mechanism of hydrogen evolution.

The organic electrochemist The organic electrochemist

In his systematic work on the reduction of organic substances, Tafel opened routes to many compounds more readily prepared by electrochemical than by chemical methods, often resulting in patents issued in the name of C. F. Boehringer Mannheim. Of special economic significance was the reduction of nitric acid to hydroxylamine, making this substance readily available for the first time (1902).

An important achievement was the preparation of certain hydrocarbons by the reduction of acetoacetic esters (1907). When some hydrocarbons produced did not exhibit the physical constants expected for them on the basis of straightforward chemistry, it turned out that an unexpected anomaly had occurred, which today is known as the Tafel rearrangement:

In other work, Tafel made first discoveries with respect to metalorganic compounds appearing during certain electrolytic reductions, where di-sec-butylmercury or unsaturated lead alkyls were produced (1911). The surprising scope of Tafel's work can be seen from the citations in Fichter's classical monograph on organic electrochemistry (1942).

Acknowledgement

This article was translated into Polish and posted in the blog of:

http://cheap.de/science/julius-tafel-jego-zycie-i-nauka.

Related articles

Jaroslav Heyrovsky and polarography

Pillars of modern electrochemistry

Walther Nernst: physicist and chemist

The Electrochemical Society: The First

Hundred Years, 1902 - 2002

Volta and the "Pile"

Bibliography

- Who Was Tafel? K. Muller, "Journal of the Research Institute for Catalysis, Hokkaido University", Vol. 17, pp 54-75, 1969.

- Organic Electrochemistry, F. Fichter, Theodor Steinkopf, Dresden/Leipzig, 1942.

- Outlines of a Theory of Proton Transfer, J. Horiuti and M. Polanyi, "Acta Physicochimica U.R.S.S.", Vol. 2, pp 505-532, 1935 (English translation: "Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical", Vol. 199, pp 185-197, 2003).

- Unsaturated Lead Alkyls, J. Tafel, "Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft", Vol. 44, pp 323-337, 1911.

- Complete Reduction of Benzylacetoacetic Ester, J. Tafel and H. Hahl, "Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft", Vol. 40, pp 3312-3318, 1907.

- A Noteworthy Way of Formation of Mercury Alkyls, J. Tafel, " Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft ", Vol. 39, pp 3626-3631, 1906.

- Cathode Potential and Electrolytic Reduction in Sulfuric Acid Solution, J. Tafel, "Zeitschrift fur Elektrochemie", Vol. 12, pp 112-122, 1906.

- The Cause of Spontaneous Depression of the Cathode Potential During Electrolysis of Diluted Sulfuric Acid, J. Tafel and B. Emmert, "Zeitschrift fur physikalische Chemie", Vol. 52, pp 349-373, 1905.

- Relationships Between Cathode Potential and Electrolytic Reduction Effect, J. Tafel and K. Naumann, "Zeitschrift fur physikalische Chemie" Vol. 50, pp 713-752, 1905.

Available on the WWW.

- On the Polarization During Cathodic Hydrogen Evolution, J. Tafel, "Zeitschrift fur physikalische Chemie", Vol. 50, pp 641-712, 1905.

Available on the WWW.

- Syntheses in the Purine and Sugar Groups, E. Fischer, Nobel Lecture 1902, English translation: http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1902/fischer-lecture.html.

- Electrolytic Reduction of Nitric Acid in the Presence of Hydrochloric or Sulfuric Acid, J. Tafel, "Zeitschrift fur anorganische und allgemeine Chemie", Vol. 31, pp 289-325, 1902.

- Hydroxylamine, C. F. Boehringer and Sohne, German Patents 133 457, 137 697, 1902.

- Products of Reduction of Uric Acid, J. Tafel, "Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft", Vol. 34, pp 258-279, 1901.

- The Electrolytic Reduction in Sulfuric Acid Solution, of Substances That Are Difficult to Reduce, J. Tafel, "Zeitschrift fur physikalische Chemie", Vol. 34, pp 187-228, 1900, and "Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft", Vol. 33, pp 2209-2224, 1900.

- On Electrolytic Gas Evolution, W. A. Caspari, "Zeitschrift fur physikalische Chemie", Vol. 30, pp 89-97, 1899.

- Strychnine, III, J. Tafel, "Liebigs Annalen der Chemie", Vol. 301, pp 285-348, 1898.

- Syntheses in the Sugar Group, E. Fischer, "Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft", Vol. 23, pp 2114-2141, 1890.

- Synthetic Experiments in Carbohydrate Chemistry, E. Fischer and J. Tafel, "Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft", Part I, Vol. 20, pp 2566-2575, 1887; Part II, Vol. 20, pp 3384-3390, 1887; Part III, Vol. 22, pp 97-191, 1888.

Listings of electrochemistry books, review chapters, proceedings volumes, and full text of some historical publications are also available in the Electrochemistry Science and Technology Information Resource (ESTIR). (http://knowledge.electrochem.org/estir/)

Return to:

Top –

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

|