Return to:

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

DIELECTRICS

William D. Brown,1 Dennis Hess,2 Vimal Desai,3 and M. Jamal Deen4

1Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Arkansas

3217 Bell Engineering Center, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA

2School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology

311 Ferst Drive, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA

3Mechanical, Materials and Aerospace Engineering, University of Central Florida

4000 Central Florida Blvd., Orlando, FL 32816, USA

4Electrical and Computer Engineering, McMaster University

1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, ON L8S 4K1, Canada

(May, 2006)

What is a dielectric? An historical perspective

|

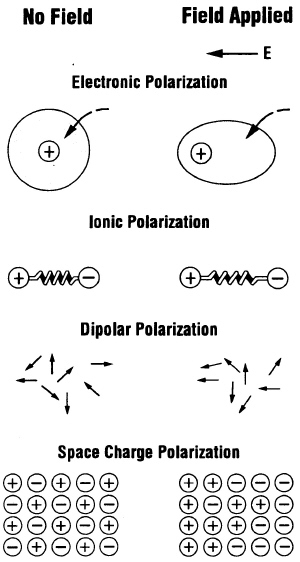

| Fig. 1. Schematic representation of different mechanisms of polarization. |

The science of dielectrics, which has

been pursued for well over one hundred

years, is one of the oldest branches of

physics and has close links to chemistry,

materials, and electrical engineering.

The term dielectric was first coined

by Faraday to suggest that there is

something analogous to current flow

through a capacitor structure during

the charging process when current

introduced at one plate (usually a metal)

flows through the insulator to charge

another plate (usually a metal). The

important consequence of imposing a

static external field across the capacitor

is that the positively and negatively

charged species in the dielectric become

polarized. Charging occurs only as the

field within the insulator is changing.

Maxwell formulated equations for

electromagnetic fields as they are

generated from displacement of electric

charges and introduced dielectric and

magnetic constants to characterize

different media. It is generally accepted

that a dielectric reacts to an electric

field differently, compared to free space,

because it contains charges that can he

displaced. Figure 1 illustrates some of the

charge configurations and their response

(polarization) under the influence of

an external field. Because almost all

material systems are made up of charges

(an exception being neutron stars!), it is

useful to characterize materials by their

dielectric constant.

|

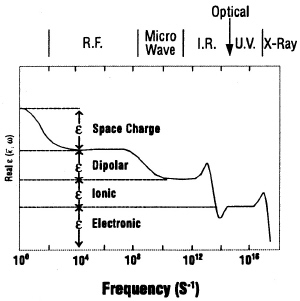

| Fig. 2. Contributions to the frequency-dependent dielectric constant from the different charge configurations. |

A schematic representation of

the real part of the dielectric constant is shown in Figure

2. At high frequencies (>1014 Hz),

the contribution comes solely from

electronic polarization, implying that

only free electrons, as in metals, can

respond to the electric field. That is why

metals are such good optical reflectors!

Even the various

thermal and mechanical properties, such

as thermal expansion, bulk modulus,

thermal conductivity, specific heat,

and refractive index, are related to the

complex dielectric constant, because

they depend on the arrangement and

mutual interaction of charges in the

material. Thus, the study of dielectrics

is fundamental in nature and offers a

unified understanding of many other

disciplines in materials science.

The scope of dielectric science and technology

|

| Table I. Core Areas of Dielectric Science and Technology |

|

| Physics/Chemistry/Materials Science |

|

- Polarizability, Relaxation, Ions, Breakdown Phenomena

- Elementary Excitations: Polaritons, Excitons, Polarons, Phonons

- Phase Transitions, Critical Phenomena

- Bonding, Ionicity, Crystal/Ligand Fields, Electronic Correlation

- Bonding, Reaction, Kinetics, Transport, Energetics, Thermodynamics

- Interfaces, Interphases

|

|

| Properties of Dielectrics |

|

- Structural/Mechanical

- Thermal

- Electrical

- Optical

- Magnetic

- Chemical

|

|

| Synthesis/Processing |

|

- Deposition: Chemical Vapor Deposition CVD, Plasma-CVD, Room Temperature (RT)CVD, Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD), Sputtering. Evaporation, Dip/Spin/Spray Coating

- Growth: Thermal, Anodic, Epitaxial

- Chemical Mechanical Planarization (CMP)

- Lithographic Processes: Photon/ Election/Ion Beam Exposure, Resist Materials

- Etching: Wet Chemical, Plasma, Reactive Ion, Ion Beam Milling Characterization

- Analytical Tools

- Modeling Manufacturing

- Monitoring/Control

- Yield

- Statistical Analysis

|

|

| Reliability |

|

- Failure Mode Analysis

- Performance Prediction

- Quality Assurance Applications

- Structural/Transportation

- Microelectronics/Optoelectronic

- Corrosion and Passivation

- Energy Production and Storage

|

|

In time, the focus on dielectric science and technology has broadened from the

materials of

the traditional dielectric films used in

semiconductor devices and capacitors,

particularly oxides and nitrides.

More recently, materials of

unique dielectric responses have been

studied and utilized in novel ways.

Table I lists many

of the core technology areas of interest to

those involved in dielectric science and

technology.

For instance, in the not too distant

past, polymer scientists and technologists

expanded their horizons from consumer

products to the high technology arena.

Particularly notable are inventions in

telecommunications, where plastic

fibers are used for short optical data

links, and polymeric films are used

for nonlinear optics applications. In

the field of microelectronics, radiation

sensitive polymers (photoresists) have

been formulated for use with a wide

variety of exposure systems, from the

early ones using visible light to those

using near ultraviolet, laser, e-beam, and

x-ray sources, for the fabrication of the

sub-micrometer structures of high speed,

high density integrated circuits. Steady

progress has also been made in the field

of passivation, where various polymeric

films are applied to microscopic objects

such as integrated circuits and the

packages that house them.

Ceramists have also extended

the range of applications; ceramic

materials are used in packages for

semiconductor integrated circuits, as well

as in automobile engines, in composites

for aerospace vehicles, and in high

efficiency power generation stations. A

notable advance was the discovery of

high-temperature superconductivity, for which Bednorz and

Muller were awarded the Nobel Prize in

Physics in 1987.

Electronic and optical engineers

are pushing the limits of the material

properties and applications of

organic and inorganic conductors,

semiconductors, and insulators. One

example is the revived interest in

diamond and diamond-like films.

These recent efforts resulted in

higher speed, higher density devices

and interconnection schemes, both

electrical and optical, for computers and

telecommunication systems. Another

example, the low-dimensional (d = 1,

2) nanostructures, which could only be

speculated about in the past, are now

a reality. This allows researchers to test

some fundamental concepts in quantum

mechanics. It is

probable that more innovative devices

will follow.

Since the mid-1990s, the

microelectronics industry has invested

heavily, with some success, in the

development of high- and low-k

dielectrics (�k� is the dielectric constant of

a material). These materials are required

because of the continuing reduction of

both horizontal and vertical dimensions

of integrated circuits (ICs), which results

in an increase of the gate leakage current,

and consequently, an increase in heat

dissipation. Therefore, high-k materials

are needed for the gate dielectric in

complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) ICs, storage capacitors,

and nonvolatile static memory devices.

Similarly, the reduction in spacing of

metal interconnects in both the vertical

and horizontal dimensions has created

the need for low-k materials that serve as

interlevel dielectrics to offset the increase

in signal propagation time between

transistors, known as RC delay (�R� is

metal wire resistance and �C� is interlevel

dielectric capacitance). As a result of

these requirements for present and future

sub-100 nm IC technologies, many

new dielectric materials and material

combinations have been and must

continue to be created and characterized

if the device density of ICs is to continue

to increase as anticipated by Moore�s

Law.

The previous discussion is not

intended to suggest that dielectric

science and technology is only important

for electronic components. Far from

it; dielectrics play important roles

in applications ranging from sensors,

isolation for conductors in the power

utility industry, to ceramic cookware.

Further, in the rapidly emerging field of

biological systems, the dielectric constant

is important because electrostatic effects

are used to link the structure and function

of biological molecules. It has been

proposed that electrostatic effects play

a major role in important biological

activities such as enzyme catalysis,

electron transfer, proton transport, ion

channels, and signal transduction. The role of the science and technology of

dielectrics is also important in existing fields of sensors,

nanotechnology, electronics, photonics,

chemical and mechanical systems, and in emerging fields of biology and

biochemistry. Thus, it appears inevitable

that the dielectric properties of nanoscale

materials and structures will be critical

to developing novel devices for current

and future commercial applications.

For example, large amounts of energy

can be stored in nanocomposites that

show large polarizabilities. In addition,

dielectric materials such as ferroelectric

and piezoelectric nanomaterials

offer significant advantages for

communication devices and data

storage systems. Recently, there have

been investigations of nanoporous

composites formed by the incorporation

of nanosize air bubbles, leading to a

significant decrease in the dielectric

constant and the ability to vary the

dielectric constant by controlling

the concentration of air bubbles.

Furthermore, the continuing trend in

miniaturization requires increasingly

thinner dielectric materials without

nanoscale defects. An understanding of

material and interfacial properties at the

nanoscale is often facilitated by materials

modeling as well as the development

of innovative characterization tools.

One such tool is the development of the

scanning nonlinear dielectric microscope

(SNDM) that can be used to measure

the microscopic point-to-point variation

of the linear and nonlinear dielectric

properties of insulators.

Future requirements and achievements

in the area of dielectrics can be realized

only by the further development and

fundamental understanding of reliable

material synthesis, processing, and

characterization technologies, making

it possible to tailor dielectric materials,

their thin film structures, and their

interfaces to specific applications.

In the past, these technologies have

been successfully applied in the

microelectronics and other industries

that depend on the unique mechanical,

optical, chemical, and electrical

properties of high performance dielectric

materials. The advent of nanoscale

devices in recent years demands that

scientists and engineers continue to

focus attention on dielectric material

design, synthesis, and characterization

for enhanced performance, reliability,

and manufacturability.

|

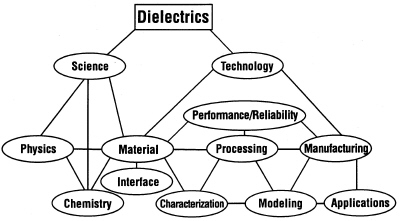

| Fig. 3. Interactions among the core areas of dielectric science and technology. |

Figure 3 is an attempt to depict

the multitude of interactions among

the many and diverse core areas of

dielectric science and technology

that present challenging possibilities

for the community of scientists,

engineers, and technologists in research,

development, and manufacturing.

Acknowledgement

This article was reproduced from The Electrochemical Society Interface (Vol. 15, No. 1, Spring 2006) with permission of The Electrochemical Society, Inc. and the authors.

Bibliography

- Material Science and Engineering for the 1990s, National Academy of Science Press, Washington, 1989.

- Introduction to Ceramics (2nd edition), W. D. Kingery, H. K. Bowen, and D. R. Uhlmann, pp 918 et seq., Wiley, New York, 1976.

- Introduction to Solid State Physics (4th edition), C. Kittel, Wiley, New York, 1971.

- Solid State Physics, Advances in Research and Applications, F. Seitz, D. Turnbull, and H. Ehrenreich, Academic Press, New York, 1969.

- Theory of Quantum Liquids, D. Pines and P. Nozieres, p. 280, Benjamin, New York, 1966.

Listings of electrochemistry books, review chapters, proceedings volumes, and full text of some historical publications are also available in the Electrochemistry Science and Technology Information Resource (ESTIR). (http://knowledge.electrochem.org/estir/)

Return to:

Top –

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

|