Return to:

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

NONRECHARGEABLE BATTERIES

Brooke Schumm

Eagle-Cliffs, Inc.

Cleveland, OH 44140, USA

(June, 2002)

Batteries - what would we do without them?

|

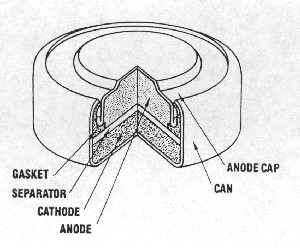

| Fig. 1. Examples of commercial Leclanche cells from the 1960's. (Courtesy Eveready Battery Co., Inc.) |

|

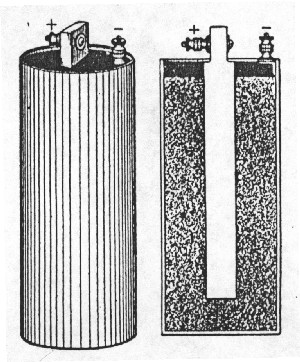

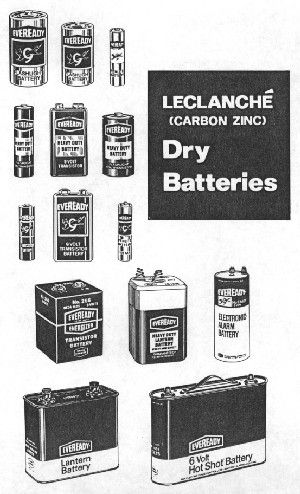

| Fig. 2. Early "6-inch" cell. (Courtesy Eveready Battery Co., Inc.) |

Let's talk about the smaller, portable kind, the ones you throw away when they don't run your toy or light your flashlight anymore. There are dozens of them, different sizes, different chemistries usually for different purposes (Figure 1). All these batteries, or more correctly, cells (if only one at a time), did not come into being all at once. In the 1880's and 1890's people needed something which would provide cheap reliable electricity even if they dropped the battery, threw it against the wall, or bounced along with it in an automobile over rough, unpaved roads. The batteries most in use then were so-called wet cells, electrodes in a ceramic or glass jar with liquid electrolyte. Some of these electrolyte solutions were corrosive and dangerous to handle. They could slosh around or pour out if the battery was overturned. The electrodes or internal contacts of batteries such as lead-acid batteries of the time sometimes would fall apart if subjected to very much jolting or vibration such as in an automobile on rough roads.

An electrical beginning

One of the first consumer batteries to be appropriately shock and vibration resistant yet inexpensive was called a "six-inch cell," or an "ignition battery," or a "telephone cell" depending on its intended use. It was, and still is, 6 inches (~15 cm) tall and 2.5 inches (~6 cm) in diameter and weighs about two pounds (~one kg). Such a battery can be purchased today but only in a few places. The early types consisted of a zinc can with a porous plaster layer next to the zinc and a one inch (~3 cm) diameter carbon rod for a center "electrode". The space between the carbon rod and the plaster separator was filled with a hard (hammered down), barely moist cathode mixture. This mixture consisted of carbon (coke, graphite), manganese-dioxide ore and a water solution of ammonium-chloride salt and zinc-chloride salt. This meant it was technically a "Leclanche" cell due to the inventor of the chemical system, Georges Leclanche (1866), but it was usually called a "carbon cell" because both the current collecting center carbon rod and part of the cathode mix were made of types of carbon products. The cell was usually closed by filling the top of the zinc can with a hard wax mixture through which the carbon dowel protruded. Thus sealed, the structure was resistant to shock and vibration and storage (shelf) life was very good. When the plaster separator was eventually replaced with a cereal-paste-coated heavy paper, each cell (Figure 2) could provide about twenty watts of direct electrical current (dc) for short periods without electrical noise.

The earliest market was for dc power for experiments and for household door bells. Then Alexander Graham Bell chose these Leclanche "carbon" cells for use in his earliest long-distance demonstrations of the telephone. In addition about this time the spark-ignition gasoline engine started to appear on the national scene. The automobile engine and small farm engines needed a reliable source of electrical power to provide the spark for ignition of the gasoline in the cylinder(s) and in some cars to power the cranking of the engine to start it. Even if the engines were started with a crank, some had no generator to provide continuous power for the ignition to keep them going. The power for the spark was provided by a box of "six-inch" dry cells. (Although lead-acid batteries as used today were known and used, their short lifetime and the need for recharging, where there were few electric power lines, slowed their adoption as the only power source in the automobile.) The automobile and the telephone market consumed millions of these "six-inch" cells until the early nineteen twenties and some telephones in rural homes had them even after WW-II. The small farm engines revolutionized the farm economy and the automobile and the telephone revolutionized society. Critical to the success of these developments was the silent presence of these low cost "dry cells."

Flashlights and flashlight batteries

|

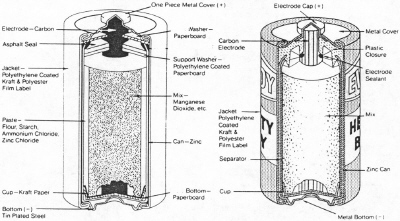

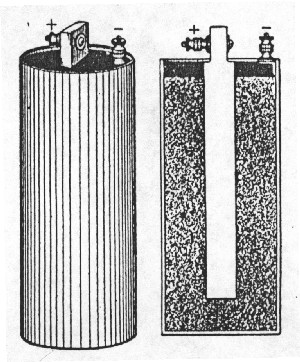

| Fig. 3. Standard and heavy-duty Leclanche cells. (Courtesy Eveready Battery Co., Inc.) |

A two pound (~one kg) Leclanche battery is a little large and heavy to carry around in one's pocket. Recognizing this, Conrad Hubert at the American Electrical Novelty and Manufacturing Company in 1898 and 1899 pioneered the use of the flashlight which was just that. It provided a relatively short flash of light for a time and then one waited for the batteries to recover. Two sizes of batteries were invented to power this type of device, "C" cells and "D" cells, as well as small light bulbs for the devices. It is said that the "C" cell is the diameter of a broom handle and the "D" cell is the diameter of a shovel handle. When the batteries and flashlights became popular, many more uses were found for the batteries and the industry grew rapidly with many companies and devices. The novelty company changed its name to American Ever Ready. The "D" and "C" batteries came to be made much like the more recent cells shown in Figure 3 but without the cell covers.

Radio batteries

|

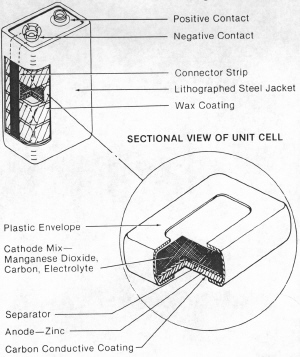

| Fig. 4. Flat Leclanche cell and battery assembly. (Courtesy Eveready Battery Co., Inc.) |

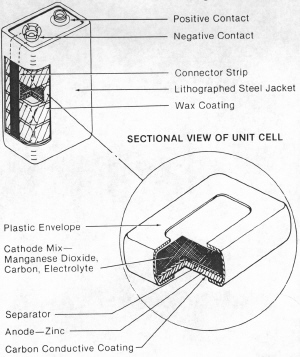

In the 1920's the electronics of the "portable" radio became practical and the use of radios attractive. They were in general larger and heavier than portable radios of today. All sizes and combinations of Leclanche batteries were built to power these radios. Many of these batteries were stacks of flat, rectangular cells, (Figure 4), each consisting of a zinc piece (the anode), a coated paper separator to place between the zinc and the manganese-dioxide mixture, the mixture of manganese-dioxide ore, graphite and the usual Leclanche solution (an aqueous solution of ammonium-chloride salt and zinc-chloride salt). The zinc was painted with a conductive paint to act as the conductor of electrons on the manganese dioxide (cathode) side of the cell. The flat cells used the space of a battery box much more efficiently than round cells. These batteries allowed the use of radios, large and small, far from any electrical power line. The time in service of this and all similar batteries, flat or cylindrical, was greatly increased when a naturally occurring manganese-dioxide ore was discovered in the country of Ghana, Africa which performed much better in dry cells than manganese-dioxide ore used up to that time.

Higher energy batteries and World War II

Mercury batteries Mercury batteries

|

| Fig. 5. Cutaway view of a miniature manganese dioxide "button" cell. (Courtesy Eveready Battery Co., Inc.) |

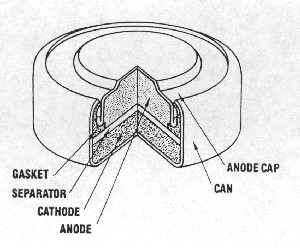

World War II brought great demands on the battery industry. Miniature batteries were needed to provide power in small devices including watches for the military. Samuel Ruben (an independent inventor) developed the zinc-mercuric oxide alkaline battery, licensed to the P.R. Mallory Co. (later Duracell, International). This battery gave five to eight times the service of a similar sized Leclanche battery. The cell was made in sizes as large as a "D" cell and yields a very reliable 1.35 volts on load rather than the constantly declining voltage of batteries with manganese-dioxide cathodes. Very few of these cells are produced now because of the manufacturing and disposal problems introduced by the presence of mercury or mercuric oxide. A modern "button" (or "coin") cell version is diagrammed in Figure 5.

Silver oxide batteries Silver oxide batteries

In the same early years of WW-II, it was realized by G. Andre that it was possible to make a practical zinc-silver oxide alkaline battery if an improved cellophane separator was placed between the zinc powder and the silver oxide-graphite mixture of the cathode. This cell is still popular for watches because it is environmentally benign (after the change to "no added" mercury in the zinc) and provides a high 1.5 volt discharge voltage for most of the time of use on relatively heavy loads.

Advances 1930 to 1960 for batteries with electrolytes based on water solutions (aqueous cells)

Leclanche cells Leclanche cells

Flashlight, toy, and radio batteries achieved about a one-hundred percent improvement in service capability when it was discovered around 1932 that the use of a special carbon black called acetylene black was possible. This carbon black was made by a special process for cracking acetylene in a retort. When it was used in a dry cell instead of graphite the service almost doubled in an optimum cathode mix formula. Unfortunately such cells tended to leak corrosive electrolyte if fully discharged, so better jacket and cover assemblies were invented including steel jackets such as marketed by Rayovac Corp. These were developed for the military in WW-II. Also in WW-II, the demand for ever more capacity by the military lead to the commercial use of synthetic manganese dioxide which was made from manganese-sulfate solutions purified for plating baths. The manganese dioxide was electrodeposited on carbon electrodes and then crushed and ground for use in premium batteries. It was a superior replacement for natural manganese-dioxide ore from Africa. This improvement in cell materials allowed the service to be doubled again in a given size battery if the need justified the additional cost for the synthetic manganese dioxide.

Zinc chloride "Heavy-Duty" cells Zinc chloride "Heavy-Duty" cells

It had been known since the 1890's that a battery like a Leclanche cell could be made without the ammonium-chloride salt and only zinc chloride for the salt in the electrolyte. However such a cell did not provide as much service or life after storage with the materials available until around 1960. At this time European and Japanese companies began to employ cell constructions that were very much better sealed to keep air out and moisture in the cells. In addition superior pastes or polymer blends were developed for coating on paper. These could withstand the more acidic zinc-chloride solution better than the earlier cereal pastes. This coated paper as a separator allowed the zinc-chloride cell to provide much higher service, especially with synthetic manganese dioxides, than previously seen. In addition it was found that the zinc-chloride cell with these separators could be made without any mercury added to the zinc anode cans and still provide satisfactory service both when new and after long shelf storage. This made this cell chemistry much more attractive to meet ever more strict commercial expectations and standards for high performance and for proper disposal of the batteries.

Alkaline zinc-manganese dioxide cells Alkaline zinc-manganese dioxide cells

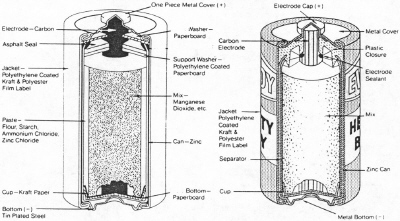

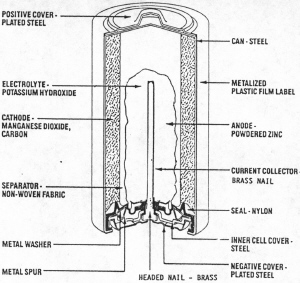

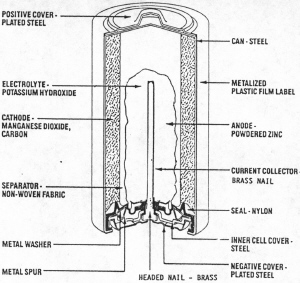

|

| Fig. 6. Cutaway view of a cylindrical alkaline cell. (Courtesy Eveready Battery Co., Inc.) |

In the late 1940's several researchers recognized that, like silver-oxide cells, zinc-manganese dioxide cells could be made to function well with an alkaline electrolyte. In order to overcome the chemical reactivity of zinc in alkaline solutions the cells were made with six to eight percent of mercury amalgamated with the zinc to control its corrosion and hydrogen gas formation in the cells. When discharged or corroded rapidly, zinc tends to form a thick oxide layer on itself in alkaline solutions. Thus the zinc used was powdered to give it more surface on which to spread out the oxide in a very thin layer. In order to use this new zinc mass consisting of zinc powder and electrolyte, a polymer thickening agent was added to the electrolyte. In order to contain this mixture in the cells, the very dry manganese dioxide-graphite mixture was placed to the outside of the cell interior in the form of a tall annular ring and encased in a steel can. A separator and the zinc anode mixture were placed in the center of the ring and the basic cell was created just as is found today. The plastic and metal seal was clamped in the top of the steel can as a seal and closure with the brass contact to the zinc anode mass projecting through the seal. A jacket and covers were placed around the basic cell and can to contain the cell and allow the addition of attractive labels and shiny metal contact covers (Figure 6). Since the 1960's the mercury content of these alkaline cells has been replaced with other benign corrosion inhibitors. (As we consider this description it is important to note that this strong construction often contains pressure. The alkaline electrolyte is a very aggressive and dangerous chemical. The cells should not be cut apart except by trained, suitably protected technicians.)

An alkaline cell like this in the "D" size could provide more heavy drain service than the early "six-inch" cells which were nine times as large. This same "D" cell could give five to ten times as much service as low cost standard Leclanche cells of the same size. Of course they are more expensive to make but actually cost less per watt of electrical power delivered for the consumer.

Magnesium-manganese dioxide cells Magnesium-manganese dioxide cells

For military applications it has also been found practical to make cells much like Leclanche batteries with a can of magnesium metal and manganese dioxide-carbon black mixture for the cathode. The electrolyte is a solution of magnesium perchlorate in water. Chromate inhibitors are added to control the corrosion of the magnesium before use. These magnesium cells when used in the Vietnam war provided better high temperature storage (shelf) life and service for many military uses. Nowadays the zinc-manganese dioxide cells have been greatly improved, so much so that the magnesium cells with the chromate chemicals are no longer of much interest for both performance and environmental disposal reasons.

Zinc-air (oxygen) cells Zinc-air (oxygen) cells

Another important class of batteries is the system where the oxygen in the air is used as a depolarizer for the cell. With this immense reservoir outside the cell for one of the chemicals, the zinc and electrolyte in the cell can be greatly increased and extraordinary service obtained from a small package. In the 1930's and into the 1980's this effect was used to make very large batteries for channel buoys and other maritime applications. More recently the system has been adapted with improved membranes to make miniature (button) cells especially for hearing aids. When properly made, the zinc-air battery can provide much more service than a zinc-silver oxide battery for lower manufacturing cost. However the cells are vulnerable to carbon dioxide from the air neutralizing the electrolyte and to drying out if the surrounding air is very dry. Thus the best applications are those like hearing aids where after the cell is unsealed, it is used continuously for a period of three to six weeks and then discarded. Like other alkaline cells the mercury in these cells has been removed so simple disposal is environmentally acceptable.

High energy batteries for the twenty first century

Lithium batteries with a solid cathode Lithium batteries with a solid cathode

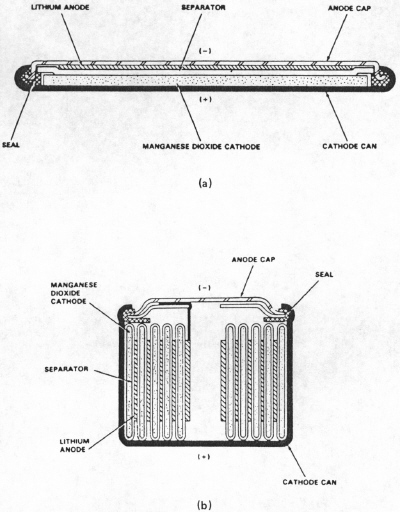

|

| Fig. 7. Lithium-manganese dioxide cell constructions: (a) miniature cell, (b) cylindrical cell. (Courtesy Eveready Battery Co., Inc.) |

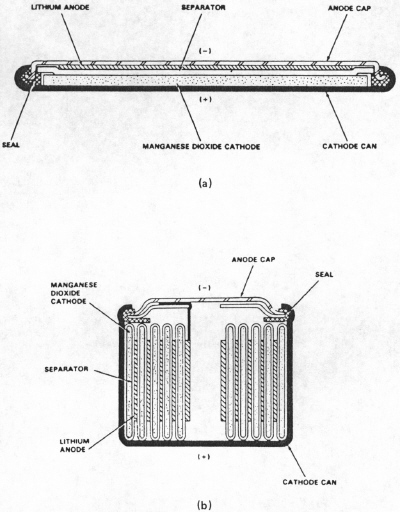

In the 1970's it became apparent that it was possible to make batteries with high-energy metals such as lithium. Lithium has an inherent voltage of 2.7 volts, enough to decompose water. Thus whatever the cathode material, the electrolyte needed to be of something besides a water solution. Such a battery and its non-water electrolyte is called a non-aqueous battery. Finding suitable mixtures of organic liquids and metal salts that were safe to use took many years. Out of this research came many different kinds of cells for all manner of applications from watches with tiny batteries to batteries large enough to power small cars. Cathode materials are varied but a special graphite with fluorine treatment and manganese dioxide are among the most common commercially for nonrechargeable cells. You can buy cylindrical lithium-manganese dioxide batteries in retail and electronics stores for especially cameras and similar devices (Figure 7). Another variation uses iron sulfide as the cathode. This powerful combination provides a 1.5 volt battery which can be directly substituted for alkaline or Leclanche (carbon-zinc) cells.

The manufacture of lithium cells and batteries is a high technology business. The cells must be assembled in rooms with relative humidity below three percent and preferably equal or less than one percent. Many major battery manufacturers have had serious factory fires when the materials of the batteries were unintentionally mishandled.

Lithium batteries with a liquid cathode Lithium batteries with a liquid cathode

In the course of study of lithium based batteries it was found that lithium forms an insulating film on its surface when it is stored in the presence of a non-aqueous electrolyte. This is particularly true if the electrolyte is a chloride compound. One such a liquid compound is called thionyl chloride. If the thionyl chloride is blended with a specially chosen carbon, it can be used as the cathode in a lithium cell without a separator, an impossible condition for an aqueous battery. This allows a very low internal cell resistance in a very high-energy package. The insulating film reforms naturally the instant the discharge of the cell ceases. Such lithium batteries can produce very high current for fairly long periods, primarily for military applications. The cells are expensive and must be assembled very carefully to avoid accidents. The cells can get very hot or even catch fire if not assembled and handled properly.

Zinc-air (oxygen) batteries Zinc-air (oxygen) batteries

The full potential of zinc-air batteries other than button cells has not been realized to the time of this writing. A computer battery available in commercial stores is a hint of things to come. This battery is about one inch (~3 cm) thick and the area of the laptop computer for which it is designed. It provides more service than a lithium battery on first use and has limited rechargeability besides. It is likely that batteries such as this will eventually become more available in "D" and "C" size cells with the use of microelectronic devices to control air and moisture access to the working internal parts.

Future developments

There is a tendency to assume that once a particular kind of battery has been invented and successfully sold as a commercial product, that no further improvement takes place in such batteries. As has been illustrated for the Leclanche cell, the discovery of new and improved materials can occur. The effect on the useful time on a given electrical load or cost of existing product such as the zinc-manganese dioxide alkaline cell can be dramatic. Year by year the useful service may be increased by two to ten percent each year. Other improvements such as the reduction of mercury content from around 0.5% to a few parts per billion have been achieved. Obviously since these cells are sold by the billions, this creates a very favorable relative environmental impact on the cost and difficulty of disposal. Hundreds of scientists and engineers are searching patiently for these and other important improvements. Their achievements benefit people worldwide as these billions of cells are sold even in the most remote locations. Similar progress is expected in the lithium and air based systems.

Another area of great promise is the marriage of electronic internal devices and cell construction. Low cost microelectronic devices and cells similar to current product can be combined to modify battery performance in valuable ways especially for zinc-air cells. Otherwise one must look to fuel cells where the active chemicals are bought in little cylinders or packages and attached to the battery to in effect recharge a battery even though the active materials are used only once.

Related articles

Current density distribution in electrochemical cells

Flow batteries

Fuel cells

PEM fuel cells

Solid oxide cells

Volta and the "Pile"

Bibliography

- Handbook of Batteries (3rd edition), D. Linden and T. B. Reddy (editors), McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001.

- Electrochemical Systems (2nd edition), J. S. Newman, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1991.

- Modern Battery Technology, C. D. S. Tuck, Ellis Horwood, Chichester, UK, 1991.

- Twenty Five Years of Progress and Future Prospects (Proceedings of the 25th Intersociety Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, Reno, NV, August 12-17, 1990, 6 volumes), P. A. Nelson, W. W. Schertz, and R. H. Till (editors), American Institute of Chemical Engineers, New York, 1990.

- Manganese Dioxide Electrode: Theory and Practice for Electrochemical

Applications (From the 166th Meeting of The Electrochemical Society, New Orleans, October 8-11, 1984, ECS Proceedings, Vol. 85-4), B. Schumm, R. L. Middaugh, M. P. Grotheer, and J. C. Hunter (editors), The Electrochemical Society, Pennington, NJ, 1985.

- Lithium Sulfur Dioxide Batteries, P. Bro and S. C. Levy, in "Lithium Battery Technology" pp 79-126, H. V. Venkatasetty (editor), Wiley, New York, 1984.

- Lithium Batteries, J.-P. Gabano (editor), Academic Press, New York, 1983.

- Small Batteries (two volumes), T. R. Crompton, Wiley, New York, 1982-1983.

- Electrochemical Power Sources, M. Barak (editor), Peter Peregrinus, New York, and Institution of Electrical Engineers, A. Wheaton and Co., Ltd. Exeter, UK, 1980.

- The Primary Battery (two volumes), N. C. Cahoon and G. H Heise (editors), Wiley, New York, 1971-1976.

- Batteries (Volume 1: Manganese Dioxide), K. V. Kordesch (editor), Marcel Dekker, New York, 1974.

- Electrochemical Kinetics, K. J. Vetter, Academic Press, New York, 1967.

- The Oxidation States of the Elements and Their Potentials in Aqueous Solutions (2nd edition), W. M. Latimer, Prentice-Hall, New York, 1952.

- Fifth Letter on Voltaic Combinations, with some Account of the Effects of a large Constant Battery, J. F. Daniell, �Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London� Vol. 129, pp 89-95, 1839. Available on the WWW.

- On Voltaic Combinations, J. F. Daniell, �Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London� Vol. 126, pp 107-124, 1836. Available on the WWW.

- M�thode pratique pour exp�rimenter un �l�ment de pile, G. Leclanch�, �Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des s�ances de l'Acad�mie des sciences, Paris� Vol. 83, pp 1236-1238, 1876. Available on the WWW.

- Nouvelle pile au peroxyde de mangan�se, G. Leclanch�, �Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des s�ances de l'Acad�mie des sciences, Paris� Vol. 83, pp 54-56, 1876. Available on the WWW.

- G. Leclanch�, French Patents, No. 69,980 and 71,865, 1866.

- On the Electricity Excited by the Mere Contact of Conducting Substances of Different Kinds (in French), A. Volta, "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London" Vol. 90, pp 403-431, 1800.

The original and a partial English translation are available on the WWW.

Listings of electrochemistry books, review chapters, proceedings volumes, and full text of some historical publications are also available in the Electrochemistry Science and Technology Information Resource (ESTIR). (http://knowledge.electrochem.org/estir/)

Return to:

Top –

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

|

Magnesium-manganese dioxide cells

Magnesium-manganese dioxide cells  Zinc-air (oxygen) cells

Zinc-air (oxygen) cells  Lithium batteries with a solid cathode

Lithium batteries with a solid cathode

Lithium batteries with a liquid cathode

Lithium batteries with a liquid cathode  Zinc-air (oxygen) batteries

Zinc-air (oxygen) batteries