Return to:

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

VOLTA AND THE "PILE"

Franco Decker

Department of Chemistry

University of Rome "La Sapienza"

P.le A.Moro 5

00185 Rome, Italy

(January, 2005)

|

The fame of Alessandro Volta (1745-1827) is due to his invention, in late 1799, of the "Pile", the first battery in history. He first named it "artificial electrical organ", because he had been trying to reproduce the behavior of the "torpedo", a selachian fish well known since the epoch of the roman philosopher Plinius (23-79, AD) for giving strong electric shocks. But how many of those using batteries today know that Volta's invention was not an isolated breakthrough, but the result of several decades of research in electricity, going back to Franklin's experiments and even before? Electric sparks and shocks were already produced at that time, in Europe and in the rest of the world, by means of the Leyden jar, a primitive but effective form of capacitor invented in 1745. In the years between 1745 and 1799, an acceleration was occurring in science and the industrial epoch was incipient. The period in which Volta lived and worked will be briefly described in the following, before we discuss the principles of the "Pile" and the way this discovery changed modern science and technology.

Volta and the "Age of Enlightenment"

In the years preceding Volta's invention, a wealth of new ideas was suddenly flourishing: while Mozart was composing his symphonies, Watts tested the first steam engine and Lavoisier formulated the law of mass conservation. Around that time, the Americans declared independence and the French revolution broke out after a rather long incubation time. Interestingly, the propagation of these revolutionary ideas, in the so-called "Age of Enlightenment", is closely related to the first Encyclopedia itself, because the publication of the "Enciclopedie des sciences et des metiers", due to titanic work of Diderot and D'Alambert, occurred in France just during the years between 1751 and 1772, when Volta grew up and started his studies.

Experiments on static electricity had become more and more popular after 1750, thanks also to the pioneering works of Benjamin Franklin, Otto von Guericke, Stephen Gray, Charles Du Fay, and to the widespread use of the Leyden jars. Demonstrations of electrostatic phenomena were held among well educated people during literary salons as well as among peasants in village fairs. In his young years Volta was studying to become a priest, like many noble young men in his time, but soon he declared he had a true passion for electricity and began his own experiments. To communicate his first scientific results, he entertained a copious correspondence with many leading authorities in this area, namely G. B. Beccaria and J.-A. Nollet. Such attitude was not unusual at that time, as the intellectual community was small. Correspondence and mutual visits among scientists and philosophers, made possible after 1750 by a relatively stable political situation in Europe, had a positive impact on the development of science because it triggered emulation, competition, and cross-fertilization between different areas of expertise. After a few years Volta established himself as physics professor, first in his home town Como and later in Pavia. During the 20 years that Volta spent as professor at the University of Pavia, he introduced the concept of electrical "tension", a correct relation between tension, charge, and capacity, and developed an impressive set of electrical apparatuses. Many of these achievements can still be seen in his cabinet in the Pavia University Museum, which can be viewed on the Museum's website (http://ppp.unipv.it/Volta/index.html).

During the same years, Luigi Galvani, a medical doctor at the famous Bologna University (the oldest university in Europe), was performing his electrical experiments with frogs and discussing his results in terms of "animal electricity". Numerous ingenious observations and experiments have been credited to him; in 1786, for example, he obtained muscular contraction in a frog by touching its nerves with a pair of scissors during an electrical storm or with the aid of an electrostatic machine. It was not the first time that animal electricity was discussed (see the torpedo fish), but it was the first time that animal's reactions and natural or man-made electricity were connected. Volta, who had developed in the meantime his own theory of the contact between dissimilar metals, had some doubts about Galvani's interpretation and committed himself to a long-lasting debate with him and with the Bologna school, rejecting the idea of an "animal electric fluid" as the source for contractions. Arguing that the frog's legs served only as an indicating electroscope, he held that the contact of dissimilar metals was the true source of stimulation. In his opinion, the electricity was generated by the bimetallic pairs and only its flow was detected by the muscle by contracting when touched by metals. His interpretation of Galvani's experiments was refuted in Bologna by obtaining muscular action with two pieces of the same material, or by touching the exposed muscle of one frog with a nerve of another. Galvani and the Bologna school had thus proven that bioelectric forces exist within living tissues, but could not demonstrate that Volta's explanation was wrong. The discussions between Volta and Galvani are a good example of the kind of competition that could break out between scientists in the "Age of Enlightenment".

This long controversy with Galvani had, in fact, provided a major stimulus for Volta to show that a durable flow of electric current can also be generated by the "mere contact of conducting substances of different kinds" (as he would write later), that is, without the use of any biological sample in the circuit. Volta was looking for something different from the simple electrostatic capacitor, which delivered strong but short sparks, and he had in mind his theory of the contact between metals. But, because the simple bimetallic contact was not enough to provide the flow of sizeable current, he had the successful idea that the interposition of a conductor of a different kind (we now call it an electrolyte) in between the two different metals would give the desired effect. This was the true key to his discovery.

The first Pile

|

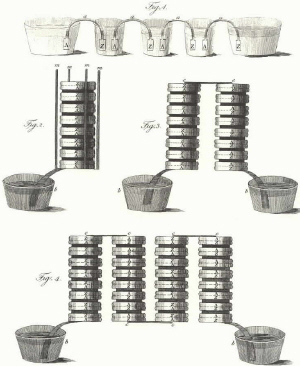

| Fig. 1. Original drawings of his Piles by Volta: the "chain of cups" apparatus (upper part), and the "columnar apparatus" (middle and lower parts). |

On the 20th of March 1800, Volta wrote a letter (in French) to Sir Joseph Banks, the president of the Royal Society of London, for publication. He reported on the construction of an electric apparatus (the Pile) that can be assembled following his detailed instructions:

"... In this manner I continue coupling a plate of silver with one of zinc, and always in the same order, that is to say, the silver below and the zinc above it, or vice versa, according as I have begun, and interpose between each of those couples a moistened disk. I continue to form, of several of this stories, a column as high as possible without any danger of its falling".

In other words, the first "electric Pile" was assembled thanks to the repetition of this modular triad constituted by a moistened disk sandwiched between two dissimilar metals. A detailed sketch of it (Figure 1) was published in Volta's paper in the September issue of the Philosophical Transactions, and shows a battery not too different from a modern battery, apart from some details. It is to be noted that the bottom- and top-most elements of the "columnar" piles shown in this figure are all Ag-Zn superposed disks. This unnecessary superposition of the two metals in the terminal electrodes (as we know today) demonstrates well Volta's personal conviction that the metal-metal, and not the metal-electrolyte interface, is the source of the electric tension giving impulsion to the current. In his view, the interposed moistened disk merely allowed to sum up the effect due to the couples of metals. Volta was conscious of the differences between the Leyden jar and his Pile and mentioned explicitly the advantages of the latter over the former. The main advantages are that the Pile gives a steady-state current (he mentioned, clearly exaggerating, a "perpetuous flow"), does not need to be previously charged and keeps its "charge", ready to use, for a long time. He drew attention to the fact that, unlike the Leyden jars having an insulating separator, the Pile is made only of conductors of different kinds and can be considered the artificial analogue of the natural electric organ of the torpedo fish. About the electric tension delivered by his Pile, Volta reported that it depends on the kind of metals used and that it increases with the number of elements added, although it can never be as high as the tension of a fully charged Leyden jar. Volta's remarks on the battery tension can be written with the modern terminology as in the equation:

E = E1 + E2 + E3 +...+ En.

That is, the overall tension is the sum of the contribution of each element and can be positive or negative depending of the order in which the metal plates are stacked in the element. Because he lacked a reliable instrument to measure such tensions, Volta had to go back to electrophysiology using his five senses to "measure" the flow of the current supplied by the Pile, and reported at length such sensations in his letter. It was clearly stated at this point that, in order to feel a strong electric shock, wet metal surfaces of the Pile had to be touched and/or wet parts of the body (the tongue, or an open wound) should be contacted. Although Volta observed and reported that salt water worked better than pure water in the moistened disks, he did not show any interest in exploring the role that the electrolyte could play in the Pile. Our modern understanding of the processes occurring in the Pile are described in the Appendix.

Success of the Pile and new developments

|

| Fig. 2. Alessandro Volta, in an engraving by G. Garavaglia (1814). |

Volta's invention became very soon a great international success: one year after his first letter to the Royal Society of London, the Institut de France invited Volta to Paris, where he was awarded with a gold medal by Napoleon who granted him a money prize as well. In the same year, Volta's Pile was reproduced by W. Nicholson and A. Carlisle who were able to obtain with it, for the first time, gaseous hydrogen and oxygen from water electrolysis. Several other chemical elements were separated and identified later by European scientists using a replica of Volta's Pile for the electrolysis: the most famous example is maybe that of H. Davy who assembled in London, with a public subscription, a battery having 2000 elements and discovered several alkali metals via electrolysis (1807-1808). In reality, the original Pile invented by Volta had some practical inconveniencies, for example, the frequent "short-circuits" between elements stacked in series due to the electrolyte spillages from the disks providing a bypass route for the current, and the hydrogen bubbles formed at the cathodes, all affecting the tension of the Pile under operation. To circumvent the first of the problems, Volta proposed a different arrangement of the conducting elements, the so-called "chain of cups" as shown in his original drawing (Figure 1), taking more space than the columnar apparatus which is associated to the name "Voltaic Pile". Other important improvements were introduced later like the introduction of "depolarizing" additives to the electrolyte, in order to reduce gas bubbles and sources of overpotential at the electrodes, or the development of gel electrolytes, to avoid the spilling of electrolyte from the moistened separators. Volta did not take part in such new developments: he was already an old man for that time and he retired from teaching and research shortly after he became famous for his invention (Figure 2). Napoleon's wars against the Austrian Empire in the first decade of 1800 ended a period of political stability in Northern Italy and triggered the upsurge of the Italian nationalistic issue. Honors and prizes won by Volta in the Napoleonic period didn't help much after the Restoration of the Austrian rule took place in Pavia in 1814 and several universities were closed for fear of student rebellions. Volta did not have pupils or active collaborators to continue his work and his intellectual legacy shifted mainly to England and France, and later to Germany, where the research on electricity was much more active than in Italy. Ampere in France, Davy and Faraday in England, Oersted in Germany opened the new era of electromagnetism with their experiments on the effects of direct electric currents. During the whole 19th century Volta's "theory of the contact" was debated and the various metals were tentatively classified according to an electrochemical series, in order to predict the tension of the Pile, but a convincing explanation of the working principles of the Pile was only given around 1890 by Nernst (the 1920

Chemistry Nobel Prize winner). An even longer time had to pass before the electrode overpotential could be explained in the frame of a theory on electrochemical reaction kinetics. Nevertheless, many different electrochemical batteries have been developed during the 19th century which all stem from the first Pile invented by Volta. Such electrical generators (by Daniell, Bunsen, Leclanche, Weston, among several others) played a fundamental role in the scientific discoveries of the 19th century. As we all know, batteries have been used widely for more than 200 years and are still essential in today's life.

Today we would not talk about the "electrical tension" of a battery or the Pile, as Volta did, rather, very befittingly, we call it the "voltage" of a battery. In 1880, the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) and the International Congress on Electricity adopted a self-consistent system of electrical units; among them, the unit of electrical potential (tension) was named the "volt", in memory of and in honor of Alessandro Volta.

Appendix

The electrochemical reactions in the Volta's Pile can be written with modern terminology, if we consider that an acidic electrolyte was used at that time, as:

| [1] |

Zn(s) ==> Zn2+(aq) + 2e- |

(at the Zn anode) |

| [2] |

2H+(aq) + 2e- ==> H2(g) |

(at the Ag cathode) |

The emf of this prototype Pile was probably around 0.75 V per element. One problem of this Pile was the gas accumulation at the cathode, considered initially to be responsible for the cell "polarization" (i.e. the fast voltage decrease under operation). Later, several efforts have been devoted to improve (or change) the cathode reaction. A substantial improvement of the Pile was introduced by Daniell, who substituted the silver cathode by a copper cathode immersed in a saturated copper sulphate solution. The cathodic reaction in the Daniell cell can be written as:

| [3] |

Cu2+(aq) + 2e- ==> Cu(s) |

(at the Cu cathode) |

The Daniell cell had a larger emf than that of Volta and was free of gaseous products. To complete this improvement, the gross mixing of the two solutions, the one near the anode (zinc sulphate in sulphuric acid) and that near the cathode, was prevented by a membrane made of a porous pot. The physical separation between the two electrolytes helped in formulating the concept that every cell reaction can be considered as the sum of two "half-reactions" occurring in the two separated compartments, named "half-cells". Following this concept, a more rigorous definition of the single electrode potential would arise, and the dependence of the electrode potential on electrolyte concentration could be studied experimentally. This represented the starting point for the formulation of the thermodynamics of electrochemical cells.

Further reading

- Science and Culture in the Age of Enlightenment, G. Pancaldi, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 2003.

- The Ambiguous Frog: The Galvani-Volta Controversy on Animal Electricity, M. Pera and J. Mandelbaum, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, 1992.

- Alessandro Volta and the Electric Battery, B. Dibner, Franklin Watts, New York, NY 1964.

- Alessandro Volta, University of Padova Available on the WWW.

- Volta and the History of Electricity, F. Bevilacqua and E. A. Giannetto (editors), Pavia Projects Physics, Available on the WWW.

- Studies on Volta and His Time, F. Bevilacqua and L. Fregonese (editors), Pavia Projects Physics, Available on the WWW.

Related articles

Nonrechargeable batteries

Jaroslav Heyrovsky and polarography

Pillars of modern electrochemistry

Walther Nernst: physicist and chemist

Julius Tafel - his life and science

The Electrochemical Society: The First

Hundred Years, 1902 - 2002

Bibliography

Listings of electrochemistry books, review chapters, proceedings volumes, and full text of some historical publications are also available in the Electrochemistry Science and Technology Information Resource (ESTIR). (http://knowledge.electrochem.org/estir/)

Return to:

Top –

Encyclopedia Home Page –

Table of Contents –

Author Index –

Subject Index –

Search –

Dictionary –

ESTIR Home Page –

ECS Home Page

|